Optimization and optimal control

These notes were originally written by T. Bretl and were transcribed by S. Bout.

Optimization

The following thing is called an optimization problem:

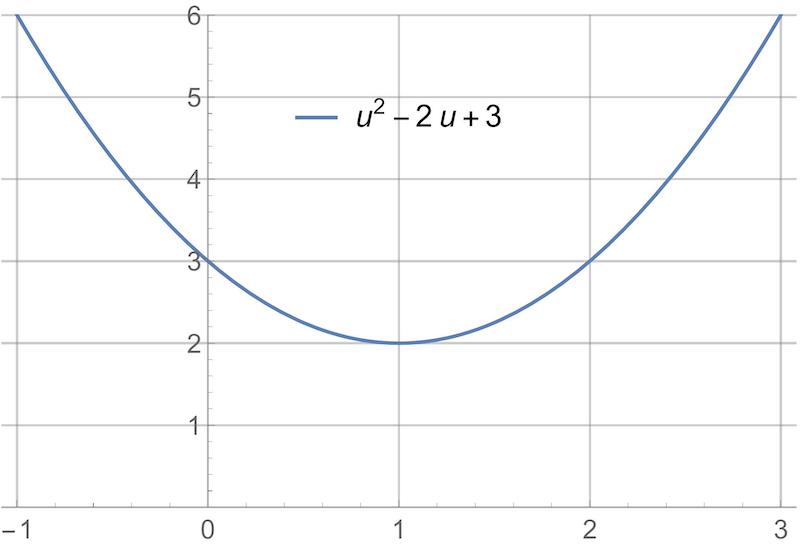

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} \qquad u^{2}-2u+3. \end{align*}\]The solution to this problem is the value of $u$ that makes $u^{2}-2u+3$ as small as possible.

-

We know that we are supposed to choose a value of $u$ because “$u$” appears underneath the “minimize” statement. We call $u$ the decision variable.

-

We know that we are supposed to minimize $u^{2}-2u+3$ because “$u^{2}-2u+3$” appears to the right of the “minimize” statement. We call $u^{2}-2u+3$ the cost function.

In particular, the solution to this problem is $u=1$. There are at least two different ways to arrive at this result:

-

We could plot the cost function. It is clear from the plot that the minimum is at $u=1$.

-

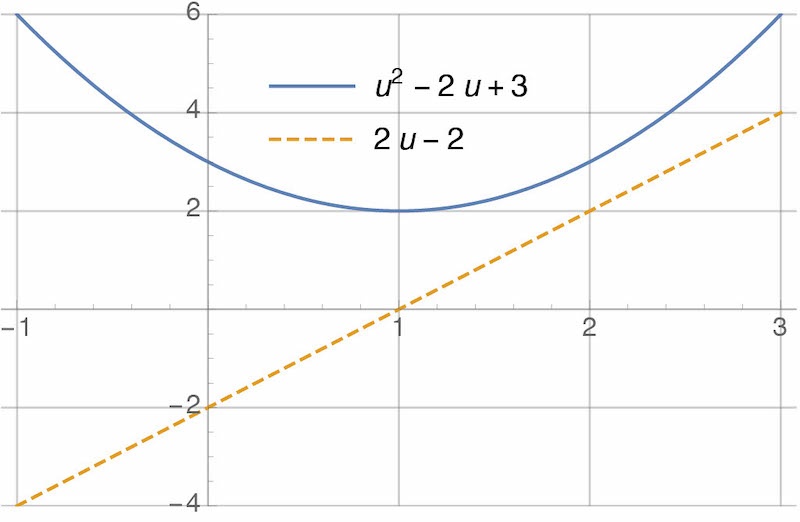

We could apply the first derivative test. We compute the first derivative:

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{d}{du} (u^{2}-2u+3) = 2 u - 2. \end{aligned}\]Then, we set the first derivative equal to zero and solve for $u$:

\[\begin{align*} 2u-2 = 0 \qquad \Rightarrow \qquad u=1. \end{align*}\]Values of $u$ that satisfy the first derivative test are only “candidates” for optimality — they could be maxima instead of minima, or could be only one of many minima. We’ll ignore this distinction for now. Here’s a plot of the cost function and of it’s derivative. Note that, clearly, the derivative is equal to zero when the cost function is minimized:

In general, we write optimization problems like this:

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} \qquad g(u). \end{align*}\]Again, $u$ is the decision variable and $g(u)$ is the cost function. In the previous example:

\[\begin{align*} g(u)=u^{2}-2u+3. \end{align*}\]Here is another example:

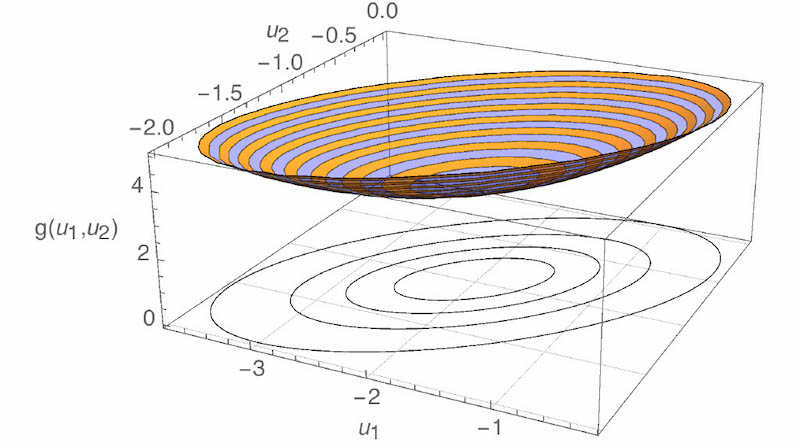

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{1},u_{2}} \qquad u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6. \end{align*}\]The solution to this problem is the value of both $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$ that, together, make

\[u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6\]as small as possible. There are two differences between this optimization problem and the previous one. First, there is a different cost function:

\[\begin{align*} g(u_{1},u_{2}) = u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6. \end{align*}\]Second, there are two decision variables instead of one. But again, there are at least two ways of finding the solution to this problem:

-

We could plot the cost function. The plot is now 3D — the “x” and “y” axes are $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$, and the “z” axis is $g(u_{1},u_{2})$. The shape of the plot is a bowl. It’s hard to tell where the minimum is from looking at the bowl, so I’ve also plotted contours of the cost function underneath. “Contours” are like the lines on a topographic map. From the contours, it looks like the minimum is at $(u_{1},u_{2})=(-2,-1)$.

-

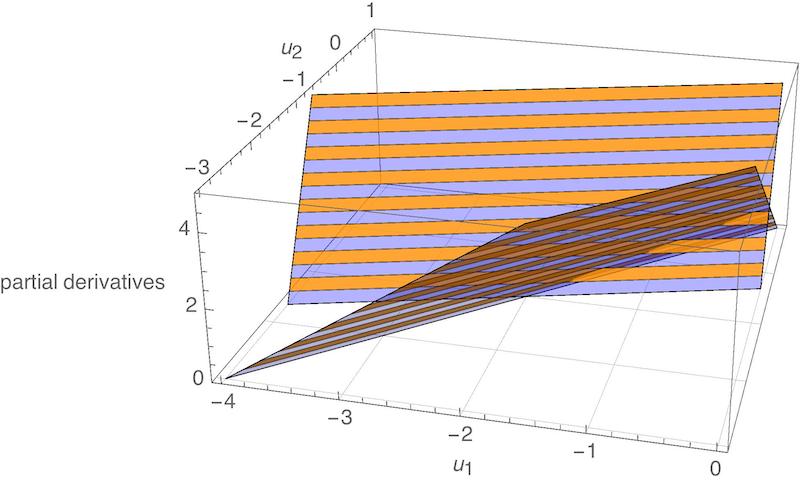

We could apply the first derivative test. We compute the partial derivative of $g(u_{1},u_{2})$ with respect to both $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$:

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial}{\partial u_{1}} g(u_{1},u_{2}) &= 2u_{1}-2u_{2}+2 \\ \frac{\partial}{\partial u_{2}} g(u_{1},u_{2}) &= 6u_{2}-2u_{1}+2.\end{aligned}\]Then, we set both partial derivatives equal to zero and solve for $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$:

\[\begin{align*} \begin{split} 2u_{1}-2u_{2}+2 &= 0\\ 6u_{2}-2u_{1}+2 &= 0 \end{split} \qquad \Rightarrow \qquad (u_{1},u_{2}) = (-2,-1). \end{align*}\]As before, we would have to apply a further test in order to verify that this choice of $(u_{1},u_{2})$ is actually a minimum. But it is certainly consistent with what we observed above. Here is a plot of each partial derivative as a function of $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$. The shape of each plot is a plane (i.e., a flat surface). Both planes are zero at $(-2,-1)$:

An equivalent way of stating this same optimization problem would have been as follows:

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{1},u_{2}} \qquad \begin{bmatrix} u_{1} \\ u_{2} \end{bmatrix}^{T} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & -1 \\ -1 & 3 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} u_{1} \\ u_{2} \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} 2 \\ 2 \end{bmatrix}^{T} \begin{bmatrix} u_{1} \\ u_{2} \end{bmatrix}+6. \end{align*}\]You can check that the cost function shown above is the same as the cost function we saw before (e.g., by multiplying it out). We could have gone farther and stated the problem as follows:

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} \qquad u^{T} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & -1 \\ -1 & 3 \end{bmatrix} u + \begin{bmatrix} 2 \\ 2 \end{bmatrix}^{T} u+6. \end{align*}\]We have returned to having just one decision variable $u$, as in the first example, but this variable is now a $2\times 1$ matrix — i.e., it has two elements, which we would normally write as $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$. The point here is that the “decision variable” in an optimization problem can be a variety of different things: a scalar, a vector (i.e., an $n\times 1$ matrix), and — as we will see — even a function of time. Before proceeding, however, let’s look at one more example of an optimization problem:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u,x} &\qquad u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad u+x=3.\end{aligned}\]This example is exactly the same as the previous example, except that the two decision variables (now renamed $u$ and $x$) are subject to a constraint:

\[u+x=3.\]We are no longer free to choose $u$ and $x$ arbitrarily. We are restricted to choices that satisfy the constraint. The solution to this optimization problem is the value $(u,x)$ that minimizes the cost function, chosen from among all values $(u,x)$ that satisfy the constraint. Again, there are a variety of ways to solve this problem. One way is to eliminate the constraint. First, we solve the constraint equation:

\[\begin{align*} u+x=3 \qquad\Rightarrow\qquad x = 3-u. \end{align*}\]Then, we plug this result into the cost function:

\[\begin{aligned} u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 &= u^{2}+3(3-u)^{2}-2u(3-u)+2u+2(3-u)+6 \\ &= 6u^{2}-24u+39.\end{aligned}\]By doing so, we have shown that solving the constrained optimization problem

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u,x} &\qquad u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad u+x=3.\end{aligned}\]is equivalent to solving the unconstrained optimization problem

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} \qquad 6u^{2}-24u+39. \end{align*}\]and then taking $x=3-u$. We can do so easily by taking the first derivative and setting it equal to zero, as we did in the first example:

\[\begin{align*} 0 = \frac{d}{du} \left(6u^{2}-24u+39\right) = 12u-24 \qquad\Rightarrow\qquad u = 2 \qquad\Rightarrow\qquad x = 3-u= 1. \end{align*}\]The point here was not to show how to solve constrained optimization problems in general, but rather to identify the different parts of a problem of this type. As a quick note, you will sometimes see the example optimization problem we’ve been considering written as

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} &\qquad u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad u+x=3.\end{aligned}\]The meaning is exactly the same, but $x$ isn’t listed as one of the decision variables under “minimize.” The idea here is that $x$ is an “extra variable” that we don’t really care about. This optimization problem is trying to say the following:

“Among all choices of $u$ for which there exists an $x$ satisfying $u+x=3$, find the one that minimizes $u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6$.”

Minimum vs. Minimizer

We have seen three example problems. In each case, we were looking for the minimizer, i.e., the choice of decision variable that made the cost function as small as possible:

-

The solution to

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} \qquad u^{2}-2u+3 \end{align*}\]was $u=1$.

-

The solution to

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{1},u_{2}} \qquad u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6 \end{align*}\]was $(u_{1},u_{2})=(-2,-1)$.

-

The solution to

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} &\qquad u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad u+x=3\end{aligned}\]was $(u,x)=(2,1)$.

It is sometimes useful to focus on the minimum instead of on the minimizer, i.e., what the “smallest value” was that we were able to achieve. When focusing on the minimum, we often use the following “set notation” instead:

-

The problem

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} \qquad u^{2}-2u+3 \end{align*}\]is rewritten

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ u^{2}-2u+3 \right\}. \end{align*}\]The meaning is to “find the minimum value of $u^{2}-2u+3$ over all choices of $u$.” The solution to this problem can be found by plugging in what we already know is the minimizer, $u=1$. In particular, we find that the solution is $2$.

-

The problem

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{1},u_{2}} \qquad u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6 \end{align*}\]is rewritten

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u_{1},u_{2}} \left\{ u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6 \right\}. \end{align*}\]Again, the meaning is to “find the minimum value of $u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6$ over all choices of $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$.” We plug in what we already know is the minimizer $(u_{1},u_{2})=(-2,-1)$ to find the solution — it is $3$.

-

The problem

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} &\qquad u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad u+x=3\end{aligned}\]is rewritten

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 \;\colon\; u+x=3 \right\}. \end{align*}\]And again, the meaning is to “find the minimum value of $u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6$ over all choices of $u$ for which there exists $x$ satisfying $u+x=3$.” Plug in the known minimizer, $(u,x)=(2,1)$, and we find that the solution is 15.

The important thing here is to understand the notation and to understand the difference between a “minimum” and a “minimizer.”

Optimal Control

Statement of the problem

The following thing is called an optimal control problem:

\[\begin{align*} \tag{1} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}} &\qquad h(x(t_{1})) + \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}g(x(t),u(t))dt \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = f(x(t),u(t)), \quad x(t_{0})=x_{0}. \end{align*}\]Let’s try to understand what it means.

-

The statement

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}} \end{align*}\]says that we are being asked to choose an input trajectory $u$ that minimizes something. Unlike in the optimization problems we saw before, the decision variable $u$ in this problem is a function of time. The notation $u_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}$ is one way of indicating this. Given an initial time $t_{0}$ and a final time $t_{1}$, we are being asked to choose the value of $u(t)$ at all times in between, i.e., for all $t\in[t_{0},t_{1}]$.

-

The statement

\[\begin{align*} \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = f(x(t),u(t)), \quad x(t_{0})=x_{0} \end{align*}\]is a constraint. It implies that we are restricted to choices of $u$ for which there exists an $x$ satisfying a given initial condition

\[\begin{align*} x(t_{0}) = x_{0} \end{align*}\]and satisfying the ordinary differential equation

\[\begin{align*} \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = f(x(t),u(t)). \end{align*}\]One example of an ordinary differential equation that looks like this is our usual description of a system in state-space form:

\[\begin{align*} \dot{x} = Ax+Bu, \end{align*}\] -

The statement

\[\begin{align*} h(x(t_{1})) + \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}g(x(t),u(t))dt \end{align*}\]says what we are trying to minimize — it is the cost function in this problem. Notice that the cost function depends on both $x$ and $u$. Part of it, $g(\cdot)$, is integrated (i.e., “added up”) over time. Part of it, $h(\cdot)$, is applied only at the final time. One example of a cost function that looks like this is

\[\begin{align*} x(t_{1})^{T}Mx(t_{1}) + \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}} \left( x(t)^{T}Qx(t)+u(t)^{T}Ru(t) \right) dt. \end{align*}\]

The HJB equation (our new “first-derivative test”)

As usual, there are a variety of ways to solve an optimal control problem. One way is by application of what is called the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman Equation, or “HJB.” This equation is to optimal control what the first-derivative test is to optimization. To derive it, we will first rewrite the optimal control problem in “minimum form” (see “Minimum vs Minimizer”):

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}} \left\{ h(x(t_{1})) + \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}g(x(t),u(t))dt \;\colon\; \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = f(x(t),u(t)), \quad x(t_{0})=x_{0} \right\}. \end{align*}\]Nothing has changed here, we’re just asking for the minimum and not the minimizer. Next, rather than solve this problem outright, we will first state a slightly different problem:

\[\begin{align*} \tag{2} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t,t_{1}]}} \left\{ h(\bar{x}(t_{1})) + \int_{t}^{t_{1}}g(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s))ds \;\colon\; \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t)=x \right\}. \end{align*}\]The two changes that I made to go from the original problem to this one are:

-

Make the initial time arbitrary (calling it $t$ instead of $t_{0}$).

-

Make the initial state arbitrary (calling it $x$ instead of $x_{0}$).

I also made three changes in notation. First, I switched from $x$ to $\bar{x}$ to avoid getting confused between $x$ as initial condition and $\bar{x}$ as state trajectory. Second, I switched from $u$ to $\bar{u}$ to be consistent with the switch from $x$ to $\bar{x}$. Third, I switched from calling time $t$ to calling time $s$ to avoid getting confused with my use of $t$ as a name for the initial time.

You should think of the problem (2) as a function itself. In goes an initial time $t$ and an initial state $x$, and out comes a minimum value. We can make this explicit by writing

\[\begin{align*} \tag{3} v(t,x) &= \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t,t_{1}]}} \Biggl\{ h(\bar{x}(t_{1})) + \int_{t}^{t_{1}}g(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s))ds \;\colon\; \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t)=x \Biggr\}. \end{align*}\]We call $v(t,x)$ the value function. Notice that $v(t_{0},x_{0})$ is the solution to the original optimal control problem that we wanted to solve — the one where the initial time is $t_{0}$ and the initial state is $x_{0}$. More importantly, notice that $v(t,x)$ satisfies the following recursion:

\[\begin{align*} \tag{4} v(t,x) &= \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t,t+\Delta t]}} \Biggl\{ v(t+\Delta t, \bar{x}(t+\Delta t)) + \int_{t}^{t+\Delta t}g(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s))ds \;\colon\; \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t)=x \Biggr\}. \end{align*}\]The reason this equation is called a “recursion” is that it expresses the function $v$ in terms of itself. In particular, it splits the optimal control problem into two parts. The first part is from time $t$ to time $t+\Delta t$. The second part is from time $t+\Delta t$ to time $t_{1}$. The recursion says that the minimum value $v(t,x)$ is the sum of the cost

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t,t+\Delta t]}} \left\{ \int_{t}^{t+\Delta t}g(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s))ds \;\colon\; \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t)=x \right\} \end{align*}\]from the first part and the cost

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t+\Delta t,t_{1}]}} \left\{ h(\bar{x}(t_{1})) + \int_{t+\Delta t}^{t_{1}}g(\bar{x}(t),\bar{u}(t))dt \;\colon\; \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t+\Delta t)=\text{blah} \right\} \end{align*}\]from the second part (where “$\text{blah}$” is whatever the state turns out to be, starting at time $t$ from start $x$ and applying the input $u_{[t,t+\Delta t]}$), which we recognize as the definition of

\[\begin{align*} v\left(t+\Delta t, \bar{x}(t+\Delta t)\right). \end{align*}\]We now proceed to approximate the terms in (4) by first-order series expansions. In particular, we have

\[\begin{aligned} v\left(t+\Delta t, \bar{x}(t+\Delta t)\right) &\approx v\left(t+\Delta t, \bar{x}(t) + \frac{d\bar{x}(t)}{dt}\Delta t\right) \\ &= v\left(t+\Delta t, x + f(x,\bar{u}(t))\Delta t\right) \\ &\approx v(t,x)+\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} \Delta t + \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,\bar{u}(t))\Delta t\end{aligned}\]and we also have

\[\begin{aligned} \int_{t}^{t+\Delta t}g(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s))ds &\approx g(\bar{x}(t),\bar{u}(t)) \Delta t \\ &= g(x,\bar{u}(t))\Delta t.\end{aligned}\]If we plug both of these into (4), we find

\[\begin{align*} v(t,x) &= \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t,t+\Delta t]}} \Biggl\{ v(t+\Delta t, \bar{x}(t+\Delta t)) + \int_{t}^{t+\Delta t}g(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s))ds \;\colon\; \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t)=x\Biggr\} \\[1em] &= \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t,t+\Delta t]}} \Biggl\{ v(t,x)+\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} \Delta t + \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,\bar{u}(t))\Delta t + g(x,\bar{u}(t))\Delta t \;\colon\; \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t)=x\Biggr\}. \end{align*}\]Notice that nothing inside the minimum depends on anything other than $t$, $x$, and $\bar{u}(t)$. So we can drop the constraint and make $\bar{u}(t)$ the only decision variable. In fact, we might as well replace $\bar{u}(t)$ simply by “$u$” since we only care about the input at a single instant in time:

\[\begin{align*} v(t,x) = \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ v(t,x)+\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} \Delta t + \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,u)\Delta t + g(x,u)\Delta t \right\}. \end{align*}\]Also, notice that

\[\begin{align*} v(t,x)+\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} \Delta t \end{align*}\]does not depend on $u$, so it can be brought out of the minimum:

\[\begin{align*} v(t,x) = v(t,x)+\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} \Delta t + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,u)\Delta t + g(x,\bar{u}(t))\Delta t\right\}. \end{align*}\]To simplify further, we can subtract $v(t,x)$ from both sides, then divide everything by $\Delta t$:

\[\begin{align*} \tag{5} 0 = \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,u) + g(x,u) \right\}. \end{align*}\]The equation is called the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman Equation, or simply the HJB equation. As you can see, it is a partial differential equation, so it needs a boundary condition. This is easy to obtain. In particular, going all the way back to the definition (3), we find that

\[\begin{align*} \tag{6} v(t_{1},x) = h(x). \end{align*}\]The importance of HJB is that if you can find a solution to (5)-(6) — that is, if you can find a function $v(t,x)$ that satisfies the partial differential equation (5) and the boundary condition (6) — then the minimizer $u$ in (5), evaluated at every time $t\in[t_{0},t_{1}]$, is the solution to the optimal control problem (1). You might object that (5) “came out of nowhere.” First of all, it didn’t. We derived it just now, from scratch. Second of all, where did the first-derivative test come from? Could you derive that from scratch? (Do you, every time you need to use it? Or do you just use it?)

Solution approach

The optimal control problem

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}} &\qquad h(x(t_{1})) + \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}g(x(t),u(t))dt \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = f(x(t),u(t)), \quad x(t_{0})=x_{0}\end{aligned}\]can be solved in two steps:

-

Find $v$:

\[\begin{align*} 0 = \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,u) + g(x,u) \right\}, \qquad v(t_{1},x) = h(x). \end{align*}\] -

Find $u$:

\[\begin{align*} u(t) = \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u}\; \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,u) + g(x,u) \qquad\qquad \text{for all } t\in[t_{0},t_{1}]. \end{align*}\]

LQR

Statement of the problem

Here is the linear quadratic regulator (LQR) problem:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}} &\qquad x(t_{1})^{T}Mx(t_{1}) + \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}\left( x(t)^{T}Qx(t)+u(t)^{T}Ru(t)\right)dt \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad \dot{x}(t) = Ax(t)+Bu(t), \quad x(t_{0})=x_{0}.\end{aligned}\]It is an optimal control problem — if you define

\[\begin{align*} f(x,u) = Ax+Bu \qquad\qquad g(x,u) = x^{T}Qx+u^{T}Ru \qquad\qquad h(x) = x^{T}Mx \end{align*}\]then you see that this problem has the same form as (1). It is called “linear” because the dynamics are those of a linear (state space) system. It is called “quadratic” because the cost is quadratic (i.e., polynomial of order at most two) in $x$ and $u$. It is called a “regulator” because the result of solving it is to keep $x$ close to zero (i.e., to keep errors small).

The matrices $Q$, $R$, and $M$ are parameters that can be used to trade off error (non-zero states) with effort (non-zero inputs). These matrices have to be symmetric ($Q=Q^{T}$, etc.), have to be the right size, and also have to satisfy the following conditions in order for the LQR problem to have a solution:

\[\begin{align*} Q \geq 0 \qquad\qquad R>0 \qquad\qquad M\geq 0. \end{align*}\]What this notation means is that $Q$ and $M$ are positive semidefinite and that $R$ is positive definite (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Positive-definite_matrix). We will ignore these terms for now, noting only that this is similar to requiring (for example) that $r>0$ in order for the function $ru^{2}$ to have a minimum.

Do the matrices $Q$, $R$, and $M$ really have to be symmetric?

Suppose $Q_\text{silly}$ is not symmetric. Define

\[Q = \frac{1}{2}\left(Q_\text{silly} + Q_\text{silly}^T\right).\]First, notice that $Q$ is symmetric:

\[\begin{align*} Q^T &= \frac{1}{2}\left(Q_\text{silly} + Q_\text{silly}^T\right)^T \\ &= \frac{1}{2}\left(Q_\text{silly}^T + Q_\text{silly}\right) && \text{because $(M + N)^T = M^T + N^T$} \\ &= \frac{1}{2}\left(Q_\text{silly} + Q_\text{silly}^T\right) && \text{because $M + N = N + M$} \\ &= Q. \end{align*}\]In fact, $Q$ — when defined in this way — is often referred to as the symmetric part of $Q_\text{silly}$.

Second, notice that we can replace $Q_\text{silly}$ with $Q$ without changing the cost:

\[\begin{align*} x^T Q x &= x^T \frac{1}{2}\left(Q_\text{silly} + Q_\text{silly}^T\right) x \\ &= \frac{1}{2} x^T Q_\text{silly} x + \frac{1}{2} x^T Q_\text{silly}^T x \\ &= \frac{1}{2} x^T Q_\text{silly} x + \frac{1}{2} \left(x^T Q_\text{silly} x\right)^T && \text{because $(MN)^T = N^TM^T$}\\ &= \frac{1}{2} x^T Q_\text{silly} x + \frac{1}{2} \left(x^T Q_\text{silly} x\right) && \text{because the transpose of a scalar is itself}\\ &= \frac{1}{2}\left(x^T Q_\text{silly} x + x^T Q_\text{silly} x \right) \\ &= x^T Q_\text{silly} x. \end{align*}\]So, it is not that $Q$, $R$, and $M$ “have to be” symmetric, it’s that they “might as well be” symmetric — if they’re not, we can replace them with matrices that are symmetric without changing the cost.

Solution to the problem

Our “Solution approach” tells us to solve the LQR problem in two steps. First, we find a function $v(t,x)$ that satisfies the HJB equation. Here is that equation, with the functions $f$, $g$, and $h$ filled in from our “Statement of the problem”:

\[\begin{align*} 0 = \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} (Ax+Bu)+x^{T}Qx+u^{T}Ru \right\}, \qquad v(t_{1},x) = x^{T}Mx. \end{align*}\]What function $v$ might solve this equation? Look at the boundary condition. At time $t_{1}$,

\[\begin{align*} v(t_{1},x) = x^{T}Mx. \end{align*}\]This function has the form

\[\begin{align*} v(t,x) = x^{T}P(t)x \end{align*}\]for some symmetric matrix $P(t)$ that satisfies $P(t_{1})=M$. So let’s “guess” that this form is the solution we are looking for, and see if it satisfies the HJB equation. Before proceeding, we need to compute the partial derivatives of $v$:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\partial v}{\partial t} = x^{T} \dot{P} x \qquad\qquad \frac{\partial v}{\partial x} = 2x^{T}P \end{align*}\]This is matrix calculus (e.g., see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matrix_calculus or Chapter A.4.1 of http://web.stanford.edu/~boyd/cvxbook/bv_cvxbook.pdf). The result on the left should surprise no one. The result on the right is the matrix equivalent of

\[\partial (px^{2}) / \partial x = 2px.\]You could check that this result is correct by considering an example. Plug these partial derivatives into HJB and we have

\[\begin{align*} \tag{7} 0 &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ 2x^{T}P (Ax+Bu)+x^{T}Qx+u^{T}Ru \right\} \\ &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ x^{T} ( 2 P A + \ Q ) x+2x^{T}PBu+u^{T}Ru \right\} \end{align*}\]To evaluate the minimum, we apply the first-derivative test (more matrix calculus!):

\[\begin{aligned} 0 &= \frac{\partial}{\partial u} \left( x^{T}(2P A + Q)x+2x^{T}PBu+u^{T}Ru \right) \\ &= 2x^{T}PB+2u^{T}R \\ &= 2 \left( B^{T}Px + Ru \right)^{T}. \end{aligned}\]This equation is easily solved:

\[\begin{align*} \tag{8} u = -R^{-1}B^{T}Px. \end{align*}\]Plugging this back into (7), we have

\[\begin{aligned} 0 &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ x^{T}(2P A + Q)x+2x^{T}PBu+u^{T}Ru \right\} \\ &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + \left( x^{T}(2P A + Q)x+2x^{T}PB(-R^{-1}B^{T}Px)+(-R^{-1}B^{T}Px)^{T}R(-R^{-1}B^{T}Px) \right) \\ &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + \left( x^{T}(2P A + Q)x-2x^{T}PBR^{-1}B^{T}Px+x^{T}PBR^{-1}B^{T}Px \right) \\ &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + x^{T}(2P A + Q)x-x^{T}PBR^{-1}B^{T}Px \\ &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + x^{T}(P A+A^{T}P + Q)x-x^{T}PBR^{-1}B^{T}Px \\[0.5em] &\qquad\qquad \dotsc\text{because } x^{T}(N+N^{T})x=2x^{T}Nx \text{ for any } N \text{ and } x\dotsc \\[0.5em] &= x^{T} \left( \dot{P} + P A+A^{T}P + Q - PBR^{-1}B^{T}P \right)x.\end{aligned}\]In order for this equation to be true for any $x$, it must be the case that

\[\begin{align*} \dot{P} = PBR^{-1}B^{T}P-P A-A^{T}P - Q. \end{align*}\]In summary, we have found that

\[\begin{align*} v(t,x) = x^{T}P x \end{align*}\]solves the HJB equation, where $P$ is found by integrating the matrix differential equation

\[\begin{align*} \dot{P} = PBR^{-1}B^{T}P-P A-A^{T}P - Q \end{align*}\]backward in time, starting from

\[\begin{align*} P(t_{1}) = M. \end{align*}\]Now that we know $v$, we can find $u$. Wait, we already did that! The minimizer in the HJB equation is (8). This choice of input has the form

\[\begin{equation} u = -Kx \end{equation}\]for

\[\begin{aligned} K = R^{-1}B^{T}P. \end{aligned}\]LQR Code

Here is how to find the solution to an LQR problem with Python:

import numpy as np

from scipy import linalg

def lqr(A, B, Q, R):

# Find the cost matrix

P = linalg.solve_continuous_are(A, B, Q, R)

# Find the gain matrix

K = linalg.inv(R) @ B.T @ P

return K