You are looking at the website for a prior offering of this course. Here is the current website:

Contents

- State space models

- The matrix exponential function

- Asymptotic stability

- Optimization and Optimal Control

- State estimation

- Optimal Observer Derivation (a.k.a the Kalman Filter, a very famous thing)

State space models

What is a state space model?

A state-space model is a set of ordinary differential equations that can be written in this form:

\[\dot{x} = Ax + Bu\]There are two variables:

- $x$ is the state

- $u$ is the input

Both variables are functions of time, so we could have written $x(t)$ and $u(t)$ — but in general, we won’t use that notation unless we need it. We use dots to indicate time derivatives, so $\dot{x}$ means $dx(t)/dt$.

The state and input may have more than one element — that is to say, they may be vectors (represented by a matrix of numbers) and not scalars (represented by a single number). Suppose, in particular, that:

- the state $x$ has $n_x$ elements

- the input $u$ has $n_u$ elements

Then, we would represent them as column matrices:

\[x = \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ \vdots \\ x_{n_x} \end{bmatrix} \qquad u = \begin{bmatrix} u_1 \\ \vdots \\ u_{n_u} \end{bmatrix}\]Taking the time derivative of a matrix is equivalent to taking the time derivative of each element of that matrix, so we would write

\[\dot{x} = \begin{bmatrix} \dot{x}_1 \\ \vdots \\ \dot{x}_{n_x} \end{bmatrix}\]The state-space model also has two constants: $A$ and $B$. If $x$ and $u$ are column matrices with (possibly) more than one element, then these constants have to be matrices as well:

- $A$ is a constant matrix of size $n_x \times n_x$

- $B$ is a constant matrix of size $n_x \times n_u$

The state space model has two key properties:

- it is linear because both $\dot{x}$ is a linear function of $x$ and $u$

- it is time-invariant because $A$ and $B$ are constant

How do I put a system in state space form?

Suppose we are given a description of a dynamic system. We would like to describe this same system with a state space model.

Remember that every state space model is linear. The equations of motion that describe a dynamic system are often nonlinear. So apparently, we will have to accept that state space models can only approximate some of the systems we want to describe.

We will use linearization to arrive at this approximation, in four steps.

Step 1. Rewrite the system as a set of first-order ordinary differential equations:

\[\dot{m} = f(m,n)\]In this expression, the variables $m$ and $n$ are functions of time and can have more than one element — in general, you should represent them as column matrices. As we said before, the function $f(\cdot)$ will often be nonlinear.

Step 2. Find an equilibrium point $m_{e}, n_{e}$ of the system by solving this equation:

\[0 = f(m_{e},n_{e})\]A solution to this equation is called an equilibrium point because if

\[m = m_e \qquad n = n_e\]then

\[\dot{m} = f(m_e, n_e) = 0\]and so $m$ remains constant. That is to say, if the system reaches an equilibrium point, then it stays there. This is an important property! The goal of almost every controller we design in this course will be to make a system reach an equilibrium point quickly and reliably.

This equation may have no solutions, in which case no equilibrium point exists for the system. This is bad. We will ignore this situation for now.

This equation also may have many solutions, in which case you have to make a choice. A good choice is whatever equilibrium point you would like your system to achieve.

Step 3. Define the state and input as follows:

\[x = m-m_{e} \qquad u = n-n_{e}\]Note that $x$ measures error — the difference between $m$ and its equilibrium value. When error is zero, the system has reached equilibrium and is doing what we want. Apparently, with this way of defining the state and the input, “control design” means choosing $u$ so that $x$ goes to zero.

Step 4. Compute $A$ and $B$ as follows:

\[A = \frac{\partial f}{\partial m}\biggr\rvert_{(m_{e},n_{e})} \qquad B = \frac{\partial f}{\partial n}\biggr\rvert_{(m_{e},n_{e})}\]Why does this make any sense? Look again at the ODEs that describe the original system:

\[\dot{m} = f(m, n)\]First, because

\[x = m - m_e\]then

\[\dot{x} = \dot{m} - 0 = \dot{m}\]So the left-hand side of the ODEs can simply be replaced with $\dot{x}$.

Now, suppose we want a linear approximation to the right-hand side of the ODEs — the function $f(m, n)$. One way to find such an approximation is to take a Taylor’s series expansion about $m_e, n_e$ up to first order:

\[\begin{aligned} f(m, n) &\approx f(m_e, n_e) + \frac{\partial f}{\partial m}\biggr\rvert_{(m_{e},n_{e})} \left( m - m_e \right) + \frac{\partial f}{\partial n}\biggr\rvert_{(m_{e},n_{e})} \left( n - n_e \right) \\ &= 0 + A x + B u \\ &= A x + B u \end{aligned}\]There you have it: “$\dot{x} = Ax + Bu$” is a first-order (i.e., linear) approximation to “$\dot{m} = f(m, n)$”.

Example (first-order)

Consider the system with dynamics that are described by the following equation of motion:

\[\dot{\omega} + 2 \omega = \tau\]Let’s apply our method to put this system in state space form.

We begin by rewriting it as a set of first-order ODEs. Lucky us, the system is already described by just one first-order ODE, so all we need to do is solve for $\dot{w}$:

\[\dot{\omega} = f(\omega, \tau) = -2\omega + \tau\]Next, we find an equilibrium point by solving

\[0 = -2 \omega_e + \tau_e\]In this case, there are many solutions. Suppose we pick this one:

\[\omega_e = 10 \qquad \tau_e = 20\]Then, we define the state and input based on this choice of equilibrium point:

\[x = \omega - \omega_e \qquad u = \tau - \tau_e\]Finally, we compute $A$ and $B$ by taking Jacobians (easy in this case because all the variables are scalars):

\[\begin{aligned} A &= \frac{\partial \left(-2\omega + \tau\right)}{\partial \omega}\biggr\rvert_{(\omega_{e},\tau_{e})} = -2 \\[1em] B &= \frac{\partial \left(-2\omega + \tau\right)}{\partial \tau}\biggr\rvert_{(\omega_{e},\tau_{e})} = 1 \end{aligned}\]The resulting state space model is

\[\begin{aligned} \dot{x} &= Ax + Bu \\ &= -2x + u \end{aligned}\]Note that the original system was linear, so there was no approximation here. We could probably have skipped most of these steps and written the system in state-space form by inspection. On the other hand, it is nice to know that the process of “linearization” still works even in this simple case.

Example (second-order)

Consider the system with dynamics that are described by the following equation of motion:

\[\ddot{q} + 3 \sin q = \tau\]Let’s apply our method to put this system in state-space form.

We begin by rewriting it as a set of first-order ODEs:

- We find the time-derivative of $q$ with highest order — in this case, $\ddot{q}$, of order 2.

- We define new variables for each time-derivative of $q$ with lower order — in this case, $\dot{q}$, the only time-derivative with order between 0 and 2. We might choose the following name for this time-derivative:

- We rewrite the original ODEs (in this case, just one) in terms of these new variables:

- We add one extra ODE for each new variable (in this case, just one extra) — this is trivial, coming from the way we defined these new variables:

- We collect the original ODEs and the extra ODEs together, if necessary solving for all of the time-derivatives (that’s not necessary here):

- Finally, we rewrite our result in the form $\dot{m} = f(m, n)$ by collecting things in column matrices as follows:

Note that, as desired, these rewritten ODEs have time derivatives that are at most of first order. Also note that all of these time-derivatives are on the left-hand side of the equations — none appear on the right-hand side.

Next, we find an equilibrium point by solving

\[\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} v \\ -3\sin q + \tau \end{bmatrix}\]There are many solutions. Suppose we pick this one:

In this case, there are many solutions. Suppose we pick this one:

\[q_e = \pi / 2 \qquad v_e = 0 \qquad \tau_e = 3\]Then, we define the state and input based on this choice of equilibrium point:

\[x = \begin{bmatrix} q - q_e \\ v - v_e \end{bmatrix} \qquad u = \begin{bmatrix}\tau - \tau_e\end{bmatrix}\]Finally, we compute $A$ and $B$ by taking Jacobians.

\[\begin{aligned} A &= \frac{\partial f}{\partial \begin{bmatrix} q \\ v \end{bmatrix}}\biggr\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \left.\begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial(v)}{\partial q} & \dfrac{\partial(v)}{\partial v} \\ \dfrac{\partial(-3\sin q + \tau)}{\partial q} & \dfrac{\partial(-3\sin q + \tau)}{\partial v} \end{bmatrix}\right\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \left.\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ -3\cos q & 0 \end{bmatrix}\right\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \\[1em] B &= \frac{\partial f}{\partial \begin{bmatrix} \tau \end{bmatrix}}\biggr\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \left.\begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial(v)}{\partial \tau} \\ \dfrac{\partial(-3\sin q + \tau)}{\partial \tau} \end{bmatrix}\right\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \left.\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}\right\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}\]The resulting state space model is

\[\begin{aligned} \dot{x} &= Ax + Bu \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}x + \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}u \end{aligned}\]The original system was nonlinear and the state space model is linear, so there must be some approximation here! As we will see, this approximation is good near the equilibrium point but can be very bad elsewhere.

The matrix exponential function

What is the matrix exponential?

The matrix exponential of a square matrix $M$ is the infinite series

\[e^M = I + M + \frac{1}{2}M^2 + \frac{1}{6}M^3 + \dotsm = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \dfrac{1}{k !} M^k\]where $I$ is the identity matrix. This series converges for any square matrix $M$.

How do I use the matrix exponential to solve a linear system?

The solution to the set of linear ODEs

\[\dot{x} = Fx\]with the initial condition

\[x(t_0) = x_0\]is

\[x(t) = e^{F (t - t_0)} x_0.\]How do we know that this solution is correct? First, let’s check that this solution satisfies the ODEs:

\[\begin{aligned} \dot{x} &= \frac{d}{dt} \left( e^{F (t - t_0)} x_0 \right) \\ &= \frac{d}{dt} \left( \left( I + F(t-t_0) + \frac{1}{2} F^2(t-t_0)^2 + \frac{1}{6} F^2(t-t_0)^3 + \dotsm \right) x_0 \right) \\ &= \frac{d}{dt} \left( I + F(t-t_0) + \frac{1}{2} F^2(t-t_0)^2 + \frac{1}{6} F^3(t-t_0)^3 + \dotsm \right) x_0 \\ &= \left( \frac{d}{dt} \left( I \right) + \frac{d}{dt} \left( F(t-t_0) \right) + \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{1}{2} F^2(t-t_0)^2 \right) + \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{1}{6} F^3(t-t_0)^3 \right) \dotsm \right) x_0 \\ &= \left( 0 + F + F^2(t-t_0) + \frac{1}{2} F^3(t-t_0) + \dotsm \right) x_0 \\ &= F \left(I + F(t-t_0) + \frac{1}{2} F^2(t-t_0)^2 + \dotsm \right) x_0 \\ &= F e^{F(t-t_0)} x_0 \end{aligned}\]Apparently, it does. Second, let’s check that this solution satisfies the initial condition:

\[\begin{aligned} x(t_0) &= e^{F(t_0 - t_0)} x_0 \\ &= e^0 x_0 \\ &= I x_0 \\ &= x_0 \end{aligned}\]Again, it does. (We might wonder if this is the only solution to the original ODEs — it is, although a proof would require more work.)

How do I use the matrix exponential to solve state space models?

Consider the state space model

\[\dot{x} = Ax + Bu\]This model does not look the same as

\[\dot{x} = Fx\]Indeed, without specifying $u$, we cannot solve for $x$ as a function of time. However, particular choices of $u$ allow us to simplify the state space model. For example, if we choose $u = 0$, then we can write

\[\begin{aligned} \dot{x} &= Ax+Bu \\ &= Ax + B \cdot (0) \\ &= Ax + 0 \\ &= Ax \end{aligned}\]and so we are right back at a linear system that can be solved with the matrix exponential. Another common choice of $u$ is

\[u = -Kx\]for some constant matrix $K$. (What would the size of $K$ have to be for us to define $u$ in this way?) This choice of $u$ is called state feedback, since the input depends on the state. If we plug this choice into our state space model, then we can write

\[\begin{aligned} \dot{x} &= Ax + Bu \\ &= Ax + B(-Kx) \\ &= (A - BK) x \end{aligned}\]and so — just like before — we are right back at a linear system that can be solved with the matrix exponential. Although this result will get us a long way, we will see how to solve state space models for other choices of input later on.

Asymptotic stability

What are eigenvalues and eigenvectors?

Consider a square matrix $F \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}$. If we can find a complex number $s \in \mathbb{C}$ and a non-zero, complex-valued vector $v \in \mathbb{C}^n$ that satisfy

\[(s I - F) v = 0\]then we call $s$ an eigenvalue of $F$ and $v$ the corresponding eigenvector of $F$. If we wanted, we could rearrange this equation to put it in a form that might be more familiar:

\[0 = (s I - F) v = s v - F v \qquad\Rightarrow\qquad F v = s v.\]One way to find eigenvalues is to solve the equation

\[\det (s I - F) = 0\]where “$\det(\cdot)$” means taking a determinant. In general, this equation will be an $n$th-order polynomial in $s$, and so will have $n$ solutions — we might call them $s_1, \dotsc, s_n$. To find an eigenvector that corresponds to each eigenvalue $s_i$, we solve

\[F v_i = s_i v_i\]for $v_i$. Note that there are many possible solutions to this equation and that eigenvectors are only unique up to a scale factor. In particular, for any real number $k \in \mathbb{R}$, we have

\[\begin{aligned} F (k v_i) &= k (F v_i) \\ &= k (s v_i) \\ &= s (k v_i). \end{aligned}\]Apparently, if $v_i$ is an eigenvector corresponding to $s_i$, then so is $k v_i$ for any $k \neq 0$. For this reason, algorithms to find eigenvectors typically normalize them to have unit length.

How do I diagonalize a square matrix?

Suppose we have found the eigenvalues $s_1, \dotsc, s_n$ and eigenvectors $v_1, \dotsc, v_n$ of a square matrix $F\in\mathbb{R}^{n \times n}$. Define the matrix

\[V = \begin{bmatrix} v_1 & \dotsm & v_n \end{bmatrix}\]with an eigenvector in each column, and also the matrix

\[\text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n) = \begin{bmatrix} s_1 & 0 & \dotsm & 0 \\ 0 & s_2 & \dotsm & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dotsm & s_n \end{bmatrix}\]with the eigenvalues along the diagonal.

Two things are true.

First, the following equality holds:

\[F V = V \text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n)\]You could easily verify this result for yourself.

Second, if $s_1, \dotsc, s_n$ are all distinct (i.e., if no two eigenvalues are the same), then the matrix $V$ is invertible. This result is harder to verify — it has to do with the fact that if the eigenvalues are distinct then the eigenvectors are linearly independent.

The key consequence of $V$ being invertible is that we can solve the above equality to write:

\[\text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n) = V^{-1} F V.\]In this case — if all eigenvalues are distinct and so the matrix of eigenvectors is invertible — we say that $F$ is diagonalizable. The process of “diagonalizing $F$” is finding the matrix $V$.

What is the matrix exponential of a diagonal matrix?

It is easy to find the matrix exponential of a diagonal matrix, starting from the definition:

\[\begin{align*} e^{\text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n)t} &= I + \text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n)t + \frac{1}{2}\left( \text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n) t \right)^2 + \dotsm \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & \dotsm & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & \dotsm & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dotsm & 1 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} s_1t & 0 & \dotsm & 0 \\ 0 & s_2t & \dotsm & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dotsm & s_nt \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} (s_1t)^2/2 & 0 & \dotsm & 0 \\ 0 & (s_2t)^2/2 & \dotsm & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dotsm & (s_nt)^2/2 \end{bmatrix} + \dotsm \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} 1 + s_1t + (s_1t)^2/2 + \dotsm & 0 & \dotsm & 0 \\ 0 & 1 + s_2t + (s_2t)^2/2 + \dotsm & \dotsm & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dotsm & 1 + s_nt + (s_nt)^2/2 + \dotsm \end{bmatrix} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} e^{s_1t} & 0 & \dotsm & 0 \\ 0 & e^{s_2t} & \dotsm & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dotsm & e^{s_nt} \end{bmatrix} \end{align*}\]What is the solution to a linear system that is diagonalizable?

We have seen that the solution to

\[\dot{x} = Fx\]with the initial condition

\[x(0) = x_0\]is

\[x(t) = e^{Ft}x_0.\]Suppose $F$ is a diagonalizable matrix, so that

\[\text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n) = V^{-1} F V\]where

\[\text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n)\]is a diagonal matrix that contains the eigenvalues of $F$ and where

\[V = \begin{bmatrix} v_1 & \dotsm & v_n \end{bmatrix}\]is a matrix of the corresponding eigenvectors. Then, applying the definition of matrix exponential again, we have

\[\begin{align*} e^{Ft}x_0 &= e^{V \text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n) V^{-1}t}x_0 \\ &= \left( I + V \text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n) V^{-1}t + \frac{1}{2}\left( V \text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n) V^{-1}t \right)^2 + \dotsm\right) x_0 \\ &= V \left( I + \text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n) t + \frac{1}{2} \left( \text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n)t \right)^2 + \dotsm\right) V^{-1}x_0 \\ &= V e^{\text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n)t}V^{-1}x_0 \\ &= V \begin{bmatrix} e^{s_1t} & 0 & \dotsm & 0 \\ 0 & e^{s_2t} & \dotsm & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dotsm & e^{s_nt} \end{bmatrix} V^{-1}x_0 \end{align*}\]where the last step comes from what we just found out about the matrix exponential of a diagonal matrix. In this expression, the terms $V$, $V^{-1}$, and $x_0$ are constant. The only terms that depend on $t$, in fact, are the scalar exponential functions

\[e^{s_1t}, \dotsc, e^{s_nt}\]that appear in the diagonal of

\[e^{\text{diag} (s_1, \dotsc, s_n)t}.\]Therefore, we can infer the behavior of $x(t)$ based entirely on these scalar exponential functions. In particular, suppose that each eigenvalue $s_i$ — a complex number — has real part $a_i$ and imaginary part $b_i$, or in other words that

\[s_i = a_i + jb_i.\]Euler’s formula tells us that

\[e^{s_it} = e^{(a_i+jb_i)t} = e^{a_it}\left(\cos(b_it) + j\sin(b_it)\right).\]Apparently, as time gets large, one of three things is true about each of these terms:

- if $a_i > 0$, then $e^{(a_i+jb_i)t}$ grows quickly

- if $a_i = 0$, then $e^{(a_i+jb_i)t}$ is constant ($b_i=0$) or is sinusoidal with constant magnitude ($b_i \neq 0$)

- if $a_i < 0$, then $e^{(a_i+jb_i)t}$ decays quickly to zero

It is possible to show that (more or less) the same result holds for any system $\dot{x}=Fx$, not only ones for which $F$ is diagonalizable. This takes more work, and involves the transformation of $F$ into Jordan normal form rather than into a diagonal matrix. We would discover that the terms that depend on $t$ all look like

\[t^me^{s_it}\]where $m$ is an integer that is at most the multiplicity of the eigenvalue $s_i$. Since $e^{a_it}$ increases or decreases a lot faster than $t^m$, then the same three things we listed above would be true of each term in $x(t)$, just like before.

See the reference textbook for details.

When is a linear system asymptotically stable?

The system

\[\dot{x} = Fx\]is called asymptotically stable if $x(t) \rightarrow 0$ as $t \rightarrow \infty$, starting from any initial condition $x(t_0) = x_0.$

Based on our observations about the solution to linear systems that are diagonalizable, we can state the following important result:

In particular, we now have a test for whether or not a controller “works.” Suppose we apply linear state feedback

\[u = -Kx\]to the state space system

\[\dot{x} = Ax + Bu\]so that

\[\dot{x} = (A - BK)x.\]The controller “works” when this system is asymptotically stable, i.e., when $x$ goes to zero as time gets large. We now know, therefore, that the controller “works” when all eigenvalues of $A - BK$ have negative real part.

We may not have a systematic way of finding a matrix $K$ to make the closed-loop system stable yet, but we certainly do have a systematic way now of deciding whether or not a given matrix $K$ makes the closed-loop system stable.

Optimization and Optimal Control

These notes were originally written by T. Bretl and were transcribed for this reference page by S. Bout.

Optimization

The following thing is called an optimization problem:

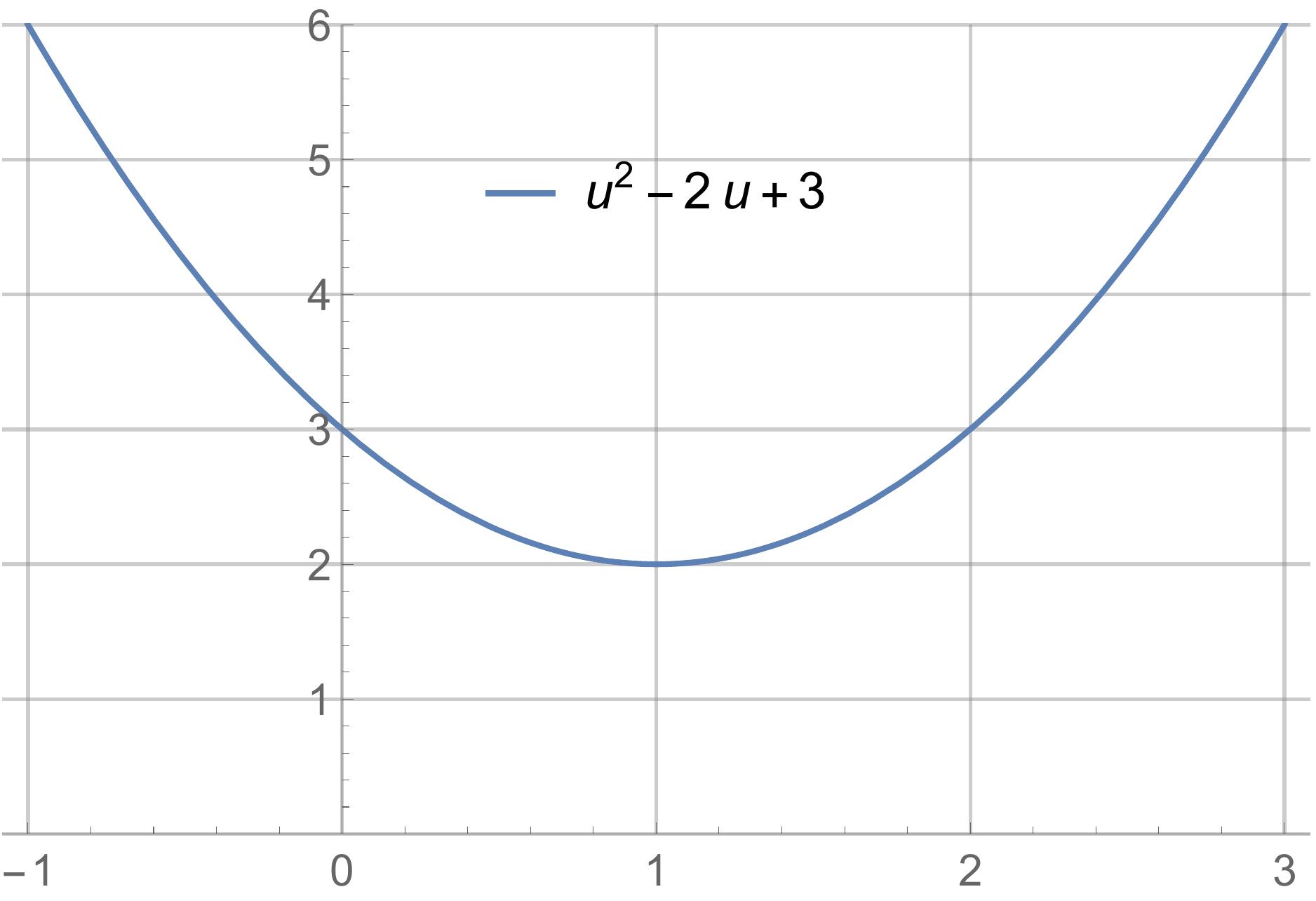

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} \qquad u^{2}-2u+3 \end{align*}\]The solution to this problem is the value of $u$ that makes $u^{2}-2u+3$ as small as possible.

-

We know that we are supposed to choose a value of $u$ because “$u$” appears underneath the “minimize” statement. We call $u$ the decision variable.

-

We know that we are supposed to minimize $u^{2}-2u+3$ because “$u^{2}-2u+3$” appears to the right of the “minimize” statement. We call $u^{2}-2u+3$ the cost function.

In particular, the solution to this problem is $u=1$. There are at least two different ways to arrive at this result:

-

We could plot the cost function. It is clear from the plot that the minimum is at $u=1$.

-

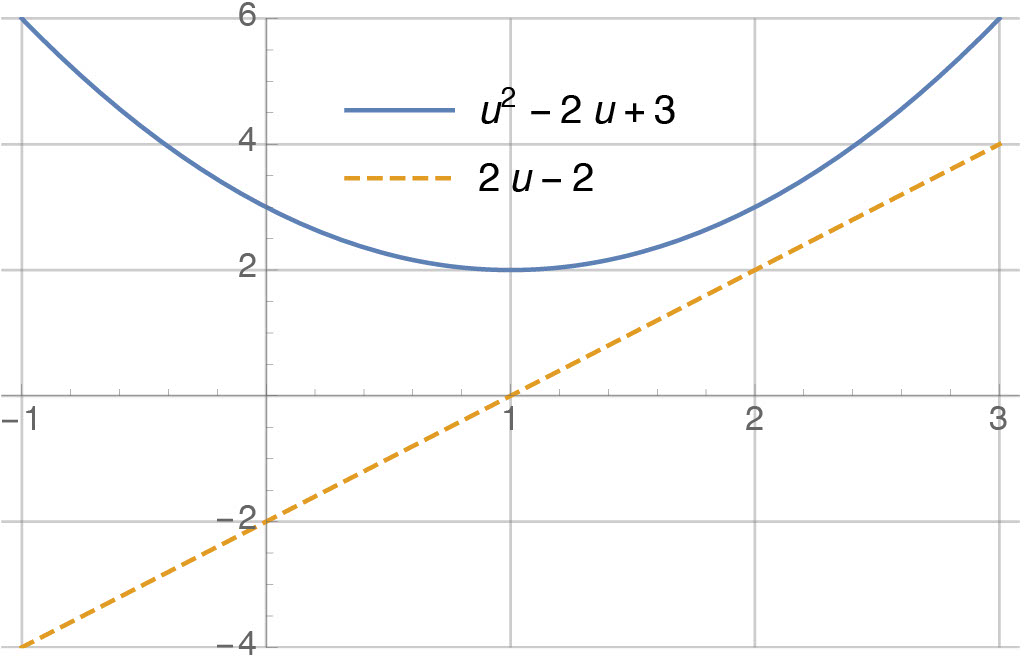

We could apply the first derivative test. We compute the first derivative:

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{d}{du} (u^{2}-2u+3) = 2 u - 2 \end{aligned}\]Then, we set the first derivative equal to zero and solve for $u$:

\[\begin{align*} 2u-2 = 0 \qquad \Rightarrow \qquad u=1 \end{align*}\]Values of $u$ that satisfy the first derivative test are only “candidates” for optimality—they could be maxima instead of minima, or could be only one of many minima. We’ll ignore this distinction for now. Here’s a plot of the cost function and of it’s derivative. Note that, clearly, the derivative is equal to zero when the cost function is minimized:

In general, we write optimization problems like this:

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} \qquad g(u) \end{align*}\]Again, $u$ is the decision variable and $g(u)$ is the cost function. In the previous example:

\[\begin{align*} g(u)=u^{2}-2u+3 \end{align*}\]Here is another example:

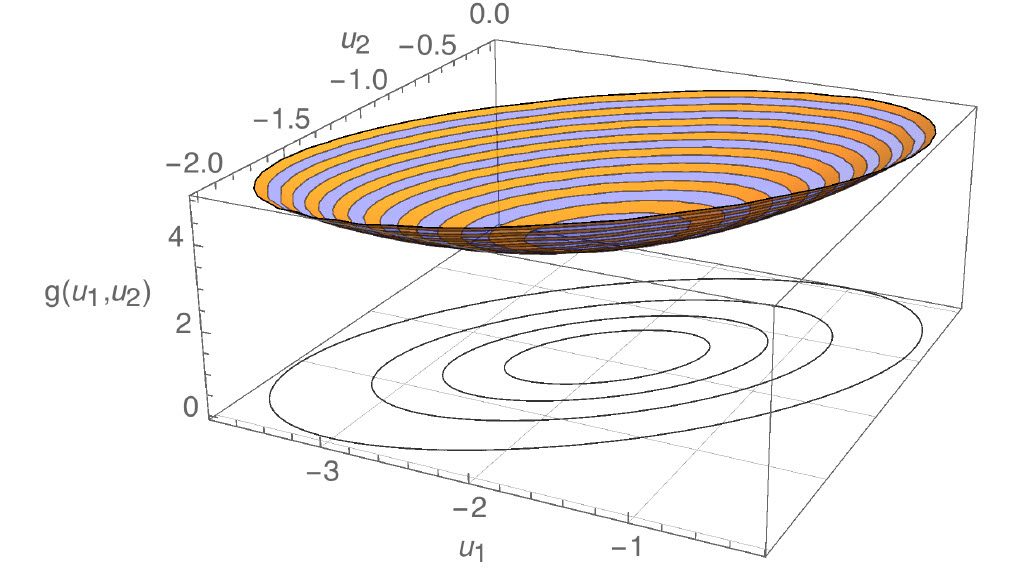

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{1},u_{2}} \qquad u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6 \end{align*}\]The solution to this problem is the value of both $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$ that, together, make $u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6$ as small as possible. There are two differences between this optimization problem and the previous one. First, there is a different cost function:

\[\begin{align*} g(u_{1},u_{2}) = u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6 \end{align*}\]Second, there are two decision variables instead of one. But again, there are at least two ways of finding the solution to this problem:

-

We could plot the cost function. The plot is now 3D—the “x” and “y” axes are $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$, and the “z” axis is $g(u_{1},u_{2})$. The shape of the plot is a bowl. It’s hard to tell where the minimum is from looking at the bowl, so I’ve also plotted contours of the cost function underneath. “Contours” are like the lines on a topographic map. From the contours, it looks like the minimum is at $(u_{1},u_{2})=(-2,-1)$.

-

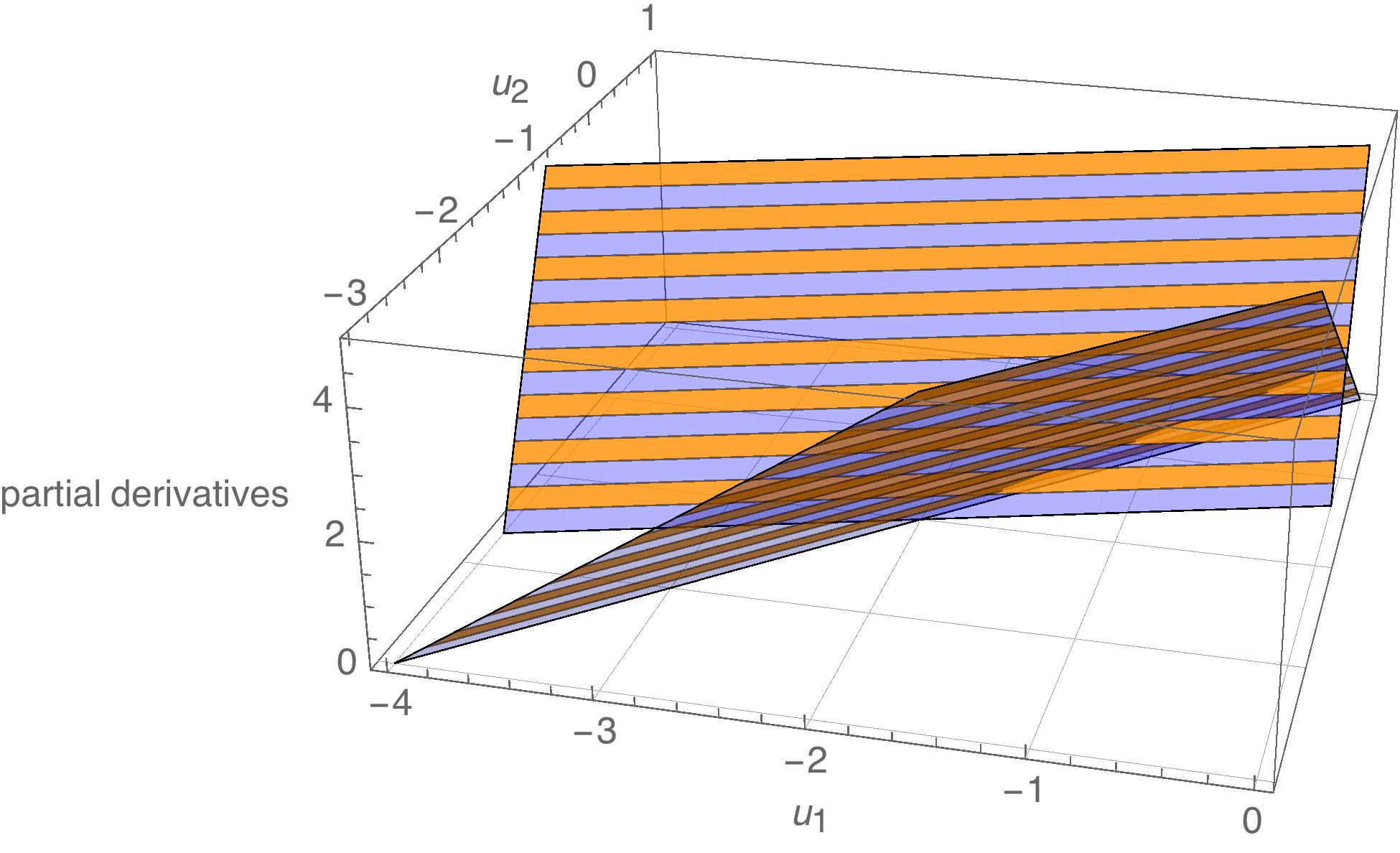

We could apply the first derivative test. We compute the partial derivative of $g(u_{1},u_{2})$ with respect to both $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$:

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial}{\partial u_{1}} g(u_{1},u_{2}) &= 2u_{1}-2u_{2}+2 \\ \frac{\partial}{\partial u_{2}} g(u_{1},u_{2}) &= 6u_{2}-2u_{1}+2\end{aligned}\]Then, we set both partial derivatives equal to zero and solve for $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$:

\[\begin{align*} \begin{split} 2u_{1}-2u_{2}+2 &= 0\\ 6u_{2}-2u_{1}+2 &= 0 \end{split} \qquad \Rightarrow \qquad (u_{1},u_{2}) = (-2,-1) \end{align*}\]As before, we would have to apply a further test in order to verify that this choice of $(u_{1},u_{2})$ is actually a minimum. But it is certainly consistent with what we observed above. Here is a plot of each partial derivative as a function of $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$. The shape of each plot is a plane (i.e., a flat surface). Both planes are zero at $(-2,-1)$:

An equivalent way of stating this same optimization problem would have been as follows:

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{1},u_{2}} \qquad \begin{bmatrix} u_{1} \\ u_{2} \end{bmatrix}^{T} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & -1 \\ -1 & 3 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} u_{1} \\ u_{2} \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} 2 \\ 2 \end{bmatrix}^{T} \begin{bmatrix} u_{1} \\ u_{2} \end{bmatrix}+6 \end{align*}\]You can check that the cost function shown above is the same as the cost function we saw before (e.g., by multiplying it out). We could have gone farther and stated the problem as follows:

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} \qquad u^{T} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & -1 \\ -1 & 3 \end{bmatrix} u + \begin{bmatrix} 2 \\ 2 \end{bmatrix}^{T} u+6 \end{align*}\]We have returned to having just one decision variable $u$, as in the first example, but this variable is now a $2\times 1$ matrix—i.e., it has two elements, which we would normally write as $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$. The point here is that the “decision variable” in an optimization problem can be a variety of different things: a scalar, a vector (i.e., an $n\times 1$ matrix), and—as we will see—even a function of time. Before proceeding, however, let’s look at one more example of an optimization problem:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u,x} &\qquad u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad u+x=3\end{aligned}\]This example is exactly the same as the previous example, except that the two decision variables (now renamed $u$ and $x$) are subject to a constraint: $u+x=3$. We are no longer free to choose $u$ and $x$ arbitrarily. We are restricted to choices that satisfy the constraint. The solution to this optimization problem is the value $(u,x)$ that minimizes the cost function, chosen from among all values $(u,x)$ that satisfy the constraint. Again, there are a variety of ways to solve this problem. One way is to eliminate the constraint. First, we solve the constraint equation:

\[\begin{align*} u+x=3 \qquad\Rightarrow\qquad x = 3-u \end{align*}\]Then, we plug this result into the cost function:

\[\begin{aligned} u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 &= u^{2}+3(3-u)^{2}-2u(3-u)+2u+2(3-u)+6 \\ &= 6u^{2}-24u+39\end{aligned}\]By doing so, we have shown that solving the constrained optimization problem

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u,x} &\qquad u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad u+x=3\end{aligned}\]is equivalent to solving the unconstrained optimization problem

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} \qquad 6u^{2}-24u+39 \end{align*}\]and then taking $x=3-u$. We can do so easily by taking the first derivative and setting it equal to zero, as we did in the first example:

\[\begin{align*} 0 = \frac{d}{du} \left(6u^{2}-24u+39\right) = 12u-24 \qquad\Rightarrow\qquad u = 2 \qquad\Rightarrow\qquad x = 3-u= 1 \end{align*}\]The point here was not to show how to solve constrained optimization problems in general, but rather to identify the different parts of a problem of this type. As a quick note, you will sometimes see the example optimization problem we’ve been considering written as

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} &\qquad u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad u+x=3\end{aligned}\]The meaning is exactly the same, but $x$ isn’t listed as one of the decision variables under “minimize.” The idea here is that $x$ is an “extra variable” that we don’t really care about. This optimization problem is trying to say the following:

“Among all choices of $u$ for which there exists an $x$ satisfying $u+x=3$, find the one that minimizes $u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6$.”

Minimum vs. Minimizer

We have seen three example problems. In each case, we were looking for the minimizer, i.e., the choice of decision variable that made the cost function as small as possible:

-

The solution to

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} \qquad u^{2}-2u+3 \end{align*}\]was $u=1$.

-

The solution to

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{1},u_{2}} \qquad u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6 \end{align*}\]was $(u_{1},u_{2})=(-2,-1)$.

-

The solution to

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} &\qquad u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad u+x=3\end{aligned}\]was $(u,x)=(2,1)$.

It is sometimes useful to focus on the minimum instead of on the minimizer, i.e., what the “smallest value” was that we were able to achieve. When focusing on the minimum, we often use the following “set notation” instead:

-

The problem

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} \qquad u^{2}-2u+3 \end{align*}\]is rewritten

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ u^{2}-2u+3 \right\}. \end{align*}\]The meaning is—find the minimum value of $u^{2}-2u+3$ over all choices of $u$. The solution to this problem can be found by plugging in what we already know is the minimizer, $u=1$. In particular, we find that the solution is $2$.

-

The problem

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{1},u_{2}} \qquad u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6 \end{align*}\]is rewritten

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u_{1},u_{2}} \left\{ u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6 \right\}. \end{align*}\]Again, the meaning is—find the minimum value of $u_{1}^{2}+3u_{2}^{2}-2u_{1}u_{2}+2u_{1}+2u_{2}+6$ over all choices of $u_{1}$ and $u_{2}$. We plug in what we already know is the minimizer $(u_{1},u_{2})=(-2,-1)$ to find the solution—it is $3$.

-

The problem

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u} &\qquad u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad u+x=3\end{aligned}\]is rewritten

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6 \;\colon\; u+x=3 \right\}. \end{align*}\]And again, the meaning is—find the minimum value of $u^{2}+3x^{2}-2ux+2u+2x+6$ over all choices of $u$ for which there exists $x$ satisfying $u+x=3$. Plug in the known minimizer, $(u,x)=(2,1)$, and we find that the solution is 15.

The important thing here is to understand the notation and to understand the difference between a “minimum” and a “minimizer.”

Optimal Control

Statement of the problem

The following thing is called an optimal control problem:

\[\begin{align*} \tag{1} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}} &\qquad h(x(t_{1})) + \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}g(x(t),u(t))dt \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = f(x(t),u(t)), \quad x(t_{0})=x_{0} \end{align*}\]Let’s try to understand what it means.

-

The statement

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}} \end{align*}\]says that we are being asked to choose an input trajectory $u$ that minimizes something. Unlike in the optimization problems we saw before, the decision variable $u$ in this problem is a function of time. The notation $u_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}$ is one way of indicating this. Given an initial time $t_{0}$ and a final time $t_{1}$, we are being asked to choose the value of $u(t)$ at all times in between, i.e., for all $t\in[t_{0},t_{1}]$.

-

The statement

\[\begin{align*} \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = f(x(t),u(t)), \quad x(t_{0})=x_{0} \end{align*}\]is a constraint. It implies that we are restricted to choices of $u$ for which there exists an $x$ satisfying a given initial condition

\[\begin{align*} x(t_{0}) = x_{0} \end{align*}\]and satisfying the ordinary differential equation

\[\begin{align*} \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = f(x(t),u(t)). \end{align*}\]One example of an ordinary differential equation that looks like this is our usual description of a system in state-space form:

\[\begin{align*} \dot{x} = Ax+Bu, \end{align*}\] -

The statement

\[\begin{align*} h(x(t_{1})) + \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}g(x(t),u(t))dt \end{align*}\]says what we are trying to minimize—it is the cost function in this problem. Notice that the cost function depends on both $x$ and $u$. Part of it—$g(\cdot)$—is integrated (i.e., “added up”) over time. Part of it—$h(\cdot)$—is applied only at the final time. One example of a cost function that looks like this is

\[\begin{align*} x(t_{1})^{T}Mx(t_{1}) + \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}} \left( x(t)^{T}Qx(t)+u(t)^{T}Ru(t) \right) dt \end{align*}\]

The HJB equation (our new “first-derivative test”)

As usual, there are a variety of ways to solve an optimal control problem. One way is by application of what is called the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman Equation, or “HJB.” This equation is to optimal control what the first-derivative test is to optimization. To derive it, we will first rewrite the optimal control problem in “minimum form” (see “Minimum vs Minimizer Section”):

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}} \left\{ h(x(t_{1})) + \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}g(x(t),u(t))dt \;\colon\; \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = f(x(t),u(t)), \quad x(t_{0})=x_{0} \right\} \end{align*}\]Nothing has changed here, we’re just asking for the minimum and not the minimizer. Next, rather than solve this problem outright, we will first state a slightly different problem:

\[\begin{align*} \tag{2} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t,t_{1}]}} \left\{ h(\bar{x}(t_{1})) + \int_{t}^{t_{1}}g(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s))ds \;\colon\; \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t)=x \right\} \end{align*}\]The two changes that I made to go from the original problem to this one are:

-

Make the initial time arbitrary (calling it $t$ instead of $t_{0}$).

-

Make the initial state arbitrary (calling it $x$ instead of $x_{0}$).

I also made three changes in notation. First, I switched from $x$ to $\bar{x}$ to avoid getting confused between $x$ as initial condition and $\bar{x}$ as state trajectory. Second, I switched from $u$ to $\bar{u}$ to be consistent with the switch from $x$ to $\bar{x}$. Third, I switched from calling time $t$ to calling time $s$ to avoid getting confused with my use of $t$ as a name for the initial time.

You should think of the problem (2) as a function itself. In goes an initial time $t$ and an initial state $x$, and out comes a minimum value. We can make this explicit by writing

\[\begin{align*} \tag{3} v(t,x) = \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t,t_{1}]}} \left\{ h(\bar{x}(t_{1})) + \int_{t}^{t_{1}}g(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s))ds \;\colon\; \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t)=x \right\} \end{align*}\]We call $v(t,x)$ the value function. Notice that $v(t_{0},x_{0})$ is the solution to the original optimal control problem that we wanted to solve—the one where the initial time is $t_{0}$ and the initial state is $x_{0}$. More importantly, notice that $v(t,x)$ satisfies the following recursion:

\[\begin{align*} \tag{4} v(t,x) = \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t,t+\Delta t]}} \{ v(t+\Delta t, \bar{x}(t+\Delta t)) + \int_{t}^{t+\Delta t}g(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s))ds\colon \\ \qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t)=x\} \end{align*}\]The reason this equation is called a “recursion” is that it expresses the function $v$ in terms of itself. In particular, it splits the optimal control problem into two parts. The first part is from time $t$ to time $t+\Delta t$. The second part is from time $t+\Delta t$ to time $t_{1}$. The recursion says that the minimum value $v(t,x)$ is the sum of the cost

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t,t+\Delta t]}} \left\{ \int_{t}^{t+\Delta t}g(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s))ds \;\colon\; \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t)=x \right\} \end{align*}\]from the first part and the cost

\[\begin{align*} \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t+\Delta t,t_{1}]}} \left\{ h(\bar{x}(t_{1})) + \int_{t+\Delta t}^{t_{1}}g(\bar{x}(t),\bar{u}(t))dt \;\colon\; \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t+\Delta t)=\text{blah} \right\} \end{align*}\]from the second part (where “$\text{blah}$” is whatever the state turns out to be, starting at time $t$ from start $x$ and applying the input $u_{[t,t+\Delta t]}$), which we recognize as the definition of

\[\begin{align*} v\left(t+\Delta t, \bar{x}(t+\Delta t)\right). \end{align*}\]We now proceed to approximate the terms in (4) by first-order series expansions. In particular, we have

\[\begin{aligned} v\left(t+\Delta t, \bar{x}(t+\Delta t)\right) &\approx v\left(t+\Delta t, \bar{x}(t) + \frac{d\bar{x}(t)}{dt}\Delta t\right) \\ &= v\left(t+\Delta t, x + f(x,\bar{u}(t))\Delta t\right) \\ &\approx v(t,x)+\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} \Delta t + \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,\bar{u}(t))\Delta t\end{aligned}\]and we also have

\[\begin{aligned} \int_{t}^{t+\Delta t}g(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s))ds &\approx g(\bar{x}(t),\bar{u}(t)) \Delta t \\ &= g(x,\bar{u}(t))\Delta t.\end{aligned}\]If we plug both of these into (4), we find

\[\begin{align*} v(t,x) = \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t,t+\Delta t]}} \{ v(t+\Delta t, \bar{x}(t+\Delta t)) + \int_{t}^{t+\Delta t}g(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s))ds\colon \\ \qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t)=x\} \\ = \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{\bar{u}_{[t,t+\Delta t]}} \{ v(t,x)+\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} \Delta t + \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,\bar{u}(t))\Delta t + g(x,\bar{u}(t))\Delta t \colon \\ \qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad \frac{d\bar{x}(s)}{ds} = f(\bar{x}(s),\bar{u}(s)), \quad \bar{x}(t)=x\}. \end{align*}\]Notice that nothing inside the minimum depends on anything other than $t$, $x$, and $\bar{u}(t)$. So we can drop the constraint and make $\bar{u}(t)$ the only decision variable. In fact, we might as well replace $\bar{u}(t)$ simply by “$u$” since we only care about the input at a single instant in time:

\[\begin{align*} v(t,x) = \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \{ v(t,x)+\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} \Delta t + \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,u)\Delta t + g(x,u)\Delta t \}. \end{align*}\]Also, notice that

\[\begin{align*} v(t,x)+\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} \Delta t \end{align*}\]does not depend on $u$, so it can be brought out of the minimum:

\[\begin{align*} v(t,x) = v(t,x)+\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} \Delta t + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \{\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,u)\Delta t + g(x,\bar{u}(t))\Delta t\}. \end{align*}\]To simplify further, we can subtract $v(t,x)$ from both sides, then divide everything by $\Delta t$:

\[\begin{align*} \tag{5} 0 = \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \{ \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,u) + g(x,u) \}. \end{align*}\]The equation is called the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman Equation, or simply the HJB equation. As you can see, it is a partial differential equation, so it needs a boundary condition. This is easy to obtain. In particular, going all the way back to the definition (3), we find that

\[\begin{align*} \tag{6} v(t_{1},x) = h(x). \end{align*}\]The importance of HJB is that if you can find a solution to (5)-(6))—that is, if you can find a function $v(t,x)$ that satisfies the partial differential equation (5) and the boundary condition (6)—then the minimizer $u$ in (5), evaluated at every time $t\in[t_{0},t_{1}]$, is the solution to the optimal control problem (1). You might object that (5) “came out of nowhere.” First of all, it didn’t. We derived it just now, from scratch. Second of all, where did the first-derivative test come from? Could you derive that from scratch? (Do you, every time you need to use it? Or do you just use it?)

Solution approach

The optimal control problem

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}} &\qquad h(x(t_{1})) + \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}g(x(t),u(t))dt \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = f(x(t),u(t)), \quad x(t_{0})=x_{0}\end{aligned}\]can be solved in two steps:

-

Find $v$:

\[\begin{align*} 0 = \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \{ \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,u) + g(x,u) \}, \qquad v(t_{1},x) = h(x) \end{align*}\] -

Find $u$:

\[\begin{align*} u(t) = \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u}\; \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(x,u) + g(x,u) \qquad\qquad \text{for all } t\in[t_{0},t_{1}] \end{align*}\]

LQR

Statement of the problem

Here is the linear quadratic regulator (LQR) problem:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{u_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}} &\qquad x(t_{1})^{T}Mx(t_{1}) + \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}}\left( x(t)^{T}Qx(t)+u(t)^{T}Ru(t)\right)dt \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad \dot{x}(t) = Ax(t)+Bu(t), \quad x(t_{0})=x_{0}\end{aligned}\]It is an optimal control problem—if you define

\[\begin{align*} f(x,u) = Ax+Bu \qquad\qquad g(x,u) = x^{T}Qx+u^{T}Ru \qquad\qquad h(x) = x^{T}Mx \end{align*}\]then you see that this problem has the same form as (1). It is called “linear” because the dynamics are those of a linear (state space) system. It is called “quadratic” because the cost is quadratic (i.e., polynomial of order at most two) in $x$ and $u$. It is called a “regulator” because the result of solving it is to keep $x$ close to zero (i.e., to keep errors small).

The matrices $Q$, $R$, and $M$ are parameters that can be used to trade off error (non-zero states) with effort (non-zero inputs). These matrices have to be symmetric ($Q=Q^{T}$, etc.), have to be the right size, and also have to satisfy the following conditions in order for the LQR problem to have a solution:

\[\begin{align*} Q \geq 0 \qquad\qquad R>0 \qquad\qquad M\geq 0. \end{align*}\]What this notation means is that $Q$ and $M$ are positive semidefinite and that $R$ is positive definite (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Positive-definite_matrix). We will ignore these terms for now, noting only that this is similar to requiring (for example) that $r>0$ in order for the function $ru^{2}$ to have a minimum.

Solution to the problem

The “Solution approach” Section tells us to solve the LQR problem in two steps. First, we find a function $v(t,x)$ that satisfies the HJB equation. Here is that equation, with the functions $f$, $g$, and $h$ filled in from the “Statement of the problem” Section:

\[\begin{align*} 0 = \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ \frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} (Ax+Bu)+x^{T}Qx+u^{T}Ru \right\}, \qquad v(t_{1},x) = x^{T}Mx. \end{align*}\]What function $v$ might solve this equation? Look at the boundary condition. At time $t_{1}$,

\[\begin{align*} v(t_{1},x) = x^{T}Mx. \end{align*}\]This function has the form

\[\begin{align*} v(t,x) = x^{T}P(t)x \end{align*}\]for some symmetric matrix $P(t)$ that satisfies $P(t_{1})=M$. So let’s “guess” that this form is the solution we are looking for, and see if it satisfies the HJB equation. Before proceeding, we need to compute the partial derivatives of $v$:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\partial v}{\partial t} = x^{T} \dot{P} x \qquad\qquad \frac{\partial v}{\partial x} = 2x^{T}P \end{align*}\]This is matrix calculus (e.g., see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matrix_calculus or Chapter A.4.1 of http://web.stanford.edu/~boyd/cvxbook/bv_cvxbook.pdf). The result on the left should surprise no one. The result on the right is the matrix equivalent of $\partial (px^{2}) / \partial x = 2px$ (you could check that this result is correct by considering an example). Plug these partial derivatives into HJB and we have

\[\begin{align*} \tag{7} 0 &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ 2x^{T}P (Ax+Bu)+x^{T}Qx+u^{T}Ru \right\} \\ &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ x^{T} ( 2 P A + \ Q ) x+2x^{T}PBu+u^{T}Ru \right\} \end{align*}\]To evaluate the minimum, we apply the first-derivative test (more matrix calculus!):

\[\begin{aligned} 0 = \frac{\partial}{\partial u} \left( x^{T}(2P A + Q)x+2x^{T}PBu+u^{T}Ru \right) \\ = 2x^{T}PB+2u^{T}R \\ = 2 \left( B^{T}Px + Ru \right)^{T}. \end{aligned}\]This equation is easily solved:

\[\begin{align*} \tag{8} u = -R^{-1}B^{T}Px. \end{align*}\]Plugging this back into (7), we have

\[\begin{aligned} 0 &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{u} \left\{ x^{T}(2P A + Q)x+2x^{T}PBu+u^{T}Ru \right\} \\ &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + \left( x^{T}(2P A + Q)x+2x^{T}PB(-R^{-1}B^{T}Px)+(-R^{-1}B^{T}Px)^{T}R(-R^{-1}B^{T}Px) \right) \\ &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + \left( x^{T}(2P A + Q)x-2x^{T}PBR^{-1}B^{T}Px+x^{T}PBR^{-1}B^{T}Px \right) \\ &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + x^{T}(2P A + Q)x-x^{T}PBR^{-1}B^{T}Px \\ &= x^{T} \dot{P} x + x^{T}(P A+A^{T}P + Q)x-x^{T}PBR^{-1}B^{T}Px \\[0.5em] &\qquad\qquad \dotsc\text{because } x^{T}(N+N^{T})x=2x^{T}Nx \text{ for any } N \text{ and } x\dotsc \\[0.5em] &= x^{T} \left( \dot{P} + P A+A^{T}P + Q - PBR^{-1}B^{T}P \right)x.\end{aligned}\]In order for this equation to be true for any $x$, it must be the case that

\[\begin{align*} \dot{P} = PBR^{-1}B^{T}P-P A-A^{T}P - Q \end{align*}\]In summary, we have found that

\[\begin{align*} v(t,x) = x^{T}P x \end{align*}\]solves the HJB equation, where $P$ is found by integrating the matrix differential equation

\[\begin{align*} \dot{P} = PBR^{-1}B^{T}P-P A-A^{T}P - Q \end{align*}\]backward in time, starting from

\[\begin{align*} P(t_{1}) = M. \end{align*}\]Now that we know $v$, we can find $u$. Wait, we already did that! The minimizer in the HJB equation is (8). This choice of input has the form

\[\begin{equation} u = -Kx \end{equation}\]for

\[\begin{aligned} K = R^{-1}B^{T}P. \end{aligned}\]LQR Code

Let’s take a look at how to implement LQR using Python. The basic method is shown below:

import numpy as np

from scipy import linalg

def lqr(A, B, Q, R):

P = linalg.solve_continous_are(A, B, Q, R) # Solves the continuous algebraic Riccati equation

K = linalg.inv(R) @ B.T @ P # Generates gain matrix

return K

State estimation

What is a state-space model with output?

All state-space models we have seen so far have had this form:

\[\dot{x} = Ax+Bu\]From now on, we will consider state-space models with this form instead:

\[\begin{align*} \dot{x} &= Ax + Bu \\ y &= Cx + Du \end{align*}\]We have added one more variable (along with the state $x$ and the input $u$):

- $y$ is the output

Like the state and the input, the output is a function of time — we will write $y(t)$ when we want to make the time-dependence explicit — and may have more than one element, so is in general a vector (represented by a matrix of numbers). Suppose, in particular, that:

- the output $y$ has $n_y$ elements

Then, we would represent it as a column matrix:

\[y = \begin{bmatrix} y_1 \\ \vdots \\ y_{n_y} \end{bmatrix}\]Like $A$ and $B$, the constants $C$ and $D$ have to be matrices:

- $C$ is a constant matrix of size $n_y \times n_x$

- $D$ is a constant matrix of size $n_y \times n_u$

The state-space model remains both linear and time-invariant, because $y$ is a linear function of $x$ and $u$ and because $C$ and $D$ are constant.

Outputs can be used to model a variety of different things. We will use them to model sensor measurements for the purpose of state estimation.

How do I linearize a sensor model?

You already know how to linearize a dynamic model:

- Rewrite the dynamic model as a set of first-order ODEs:

- Choose an equilibrium point $m_e, n_e$ among the solutions to this equation:

- Define the state and input in terms of the equilibrium point:

- Compute $A$ and $B$ as the Jacobian of $f$ with respect to $m$ and $n$ respectively, evaluated at the equilibrium point:

The result is a linear approximation

\[\dot{x} = Ax + Bu\]to the nonlinear dynamic model

\[\dot{m} = f(m, n)\]that is accurate near the equilibrium point.

We can use the same process to linearize a sensor model:

Step 1. Rewrite the sensor model as follows:

\[o = g(m, n).\]In this expression, the variable $o$ is a vector of sensor measurements. It is a function of time and can have more than one element — so, just like $m$ and $n$, it should be represented as a column matrix. Just like the function $f(m, n)$ that describes the dynamic model, the function $g(m, n)$ that describes the sensor model will often be nonlinear.

Step 2. Define the output as follows:

\[y = o - g(m_e, n_e).\]Note that $y$ measures the difference between what the sensor measurements are and what these measurements would be if the system were at equilibrium. In particular, the output is zero when the system is at equilibrium even if the measurements are not.

Step 3. Compute $C$ and $D$ as follows:

\[C = \frac{\partial g}{\partial m}\biggr\rvert_{(m_{e},n_{e})} \qquad\qquad D = \frac{\partial g}{\partial n}\biggr\rvert_{(m_{e},n_{e})}.\]Why does this make sense? Just like we took a first-order Taylor’s series expansion about $m_e, n_e$ to approximate the function $f(m, n)$ that describes the dynamic model, let’s take a first-order series expansion about $m_e, n_e$ to approximate the function $g(m, n)$ that describes the sensor model:

\[\begin{aligned} y &= o - g(m_e, n_e) \\ &= g(m, n) - g(m_e, n_e) \\ &\approx \left( g(m_e, n_e) + \frac{\partial g}{\partial m}\biggr\rvert_{(m_{e},n_{e})} \left( m - m_e \right) + \frac{\partial g}{\partial n}\biggr\rvert_{(m_{e},n_{e})} \left( n - n_e \right) \right) - g(m_e, n_e) \\ &= \frac{\partial g}{\partial m}\biggr\rvert_{(m_{e},n_{e})} \left( m - m_e \right) + \frac{\partial g}{\partial n}\biggr\rvert_{(m_{e},n_{e})} \left( n - n_e \right) \\ &= C x + D u \end{aligned}\]So, with this choice of $C$ and $D$, we have produced a linear approximation

\[y = Cx + Du\]to the nonlinear sensor model

\[o = g(m, n)\]that is accurate near the equilibrium point.

Example (linear sensor model)

Consider again a system with the following dynamic model:

\[\ddot{q} + 3\sin q = \tau.\]We already showed how to rewrite this dynamic model as

\[\begin{bmatrix} \dot{q} \\ \dot{v} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} v \\ -3\sin q + \tau \end{bmatrix}\]and how to linearize it about the equilibrium point

\[q_e = \pi / 2 \qquad v_e = 0 \qquad \tau_e = 3\]to produce the state-space model

\[\dot{x} = Ax+Bu\]where

\[A = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \qquad\qquad B = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}\]and

\[x = \begin{bmatrix} q - q_e \\ v - v_e \end{bmatrix} \qquad\qquad u = \begin{bmatrix}\tau - \tau_e\end{bmatrix}.\]Now suppose we have sensors that allow the measurement of

\[q.\]Let’s apply our method to put this measurement in state-space form.

First, we rewrite the measurement in the form $o = g(m, n)$, i.e., as a vector-valued function of $m$ and $n$:

\[o = \begin{bmatrix} q \end{bmatrix}.\]Then, we define the output as the difference between the value of this function and what the value would be at equilibrium:

\[\begin{aligned} y &= o - g\left( \begin{bmatrix} q_e \\ v_e \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} \tau_e \end{bmatrix} \right) \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} q \end{bmatrix} - \begin{bmatrix} q_e \end{bmatrix} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} q - q_e \end{bmatrix}. \end{aligned}\]Finally, we compute $C$ and $D$ by taking Jacobians:

\[\begin{aligned} C &= \frac{\partial g}{\partial \begin{bmatrix} q \\ v \end{bmatrix}}\biggr\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \left.\begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial(q)}{\partial q} & \dfrac{\partial(q)}{\partial v} \end{bmatrix}\right\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \left.\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\right\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \\[1em] D &= \frac{\partial g}{\partial \begin{bmatrix} \tau \end{bmatrix}}\biggr\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \left.\begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial(q)}{\partial \tau} \end{bmatrix}\right\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \left.\begin{bmatrix} 0 \end{bmatrix}\right\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}\]The resulting state-space model is

\[\begin{aligned} y &= Cx + Du \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}x + \begin{bmatrix} 0 \end{bmatrix}u. \end{aligned}\]Note that the original sensor model was linear, so there was no approximation here. We could probably have skipped the entire process of linearization and written the system in state-space form bny inspection. However, just as was true when putting dynamic models in state-space form (see example), it is nice to know that “linearization” still works even in this simple case.

Example (nonlinear sensor model)

Consider a system with the same dynamic model as before, but now suppose we have sensors that allow the measurement of

\[\dfrac{\cos q}{\sin q}.\]Again, let’s apply our method to put this measurement in state-space form.

First, we rewrite the measurement in the form $o = g(m, n)$, i.e., as a vector-valued function of $m$ and $n$:

\[o = \begin{bmatrix} \cos q / \sin q \end{bmatrix}.\]Then, we define the output as the difference between the value of this function and what the value would be at equilibrium:

\[\begin{aligned} y &= o - g\left( \begin{bmatrix} q_e \\ v_e \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} \tau_e \end{bmatrix} \right) \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} \cos q / \sin q \end{bmatrix} - \begin{bmatrix} \cos q_e / \sin q_e \end{bmatrix} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} (\cos q / \sin q) - (\cos q_e / \sin q_e) \end{bmatrix}. \end{aligned}\]Finally, we compute $C$ and $D$ by taking Jacobians:

\[\begin{aligned} C &= \frac{\partial g}{\partial \begin{bmatrix} q \\ v \end{bmatrix}}\biggr\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \left.\begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial(\cos q / \sin q)}{\partial q} & \dfrac{\partial(\cos q / \sin q)}{\partial v} \end{bmatrix}\right\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \left.\begin{bmatrix} -1 / (\sin q)^2 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\right\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} -1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \\[1em] D &= \frac{\partial g}{\partial \begin{bmatrix} \tau \end{bmatrix}}\biggr\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \left.\begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial(\cos q / \sin q)}{\partial \tau} \end{bmatrix}\right\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \left.\begin{bmatrix} 0 \end{bmatrix}\right\rvert_{\left(\begin{bmatrix}q_e\\v_e\end{bmatrix},\begin{bmatrix}\tau_{e}\end{bmatrix}\right)} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}\]The resulting state-space model is

\[\begin{aligned} y &= Cx + Du \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} -1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}x + \begin{bmatrix} 0 \end{bmatrix}u. \end{aligned}\]Optimal Observer Derivation (a.k.a the Kalman Filter, a very famous thing)

These notes were originally written by T. Bretl and were transcribed for this reference page by S. Bout.

Statement of the problem

Here is the deterministic, finite-horizon, continuous-time Kalman Filter (KF) problem—i.e., the optimal control problem that one would solve to produce an optimal observer:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{x(t_{1}),n_{[t_{0},t_{1}]},d_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}} &\qquad n(t_{0})^{T}M_{o}n(t_{0})+ \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}} \left( n(t)^{T}Q_{o}n(t)+d(t)^{T}R_{o}d(t) \right) dt \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad \dot{x}(t) = Ax(t)+Bu(t)+d(t) \\ &\qquad y(t) = Cx(t)+n(t)\end{aligned}\]The interpretation of this problem is as follows. The current time is $t_{1}$. You have taken measurements $y(t)$ over the time interval $[t_{0}, t_{1}]$. You are looking for noise $n(t)$ and disturbance $d(t)$ over this same time interval and for an estimate $x(t_{1})$ of the current state that would best explain these measurements.

The matrices $Q_{o}$, $R_{o}$, and $M_{o}$ are parameters that can be used to trade off noise (the difference between the measurements and what you expect them to be) with disturbance (the difference between the time derivative of the state and what you expect it to be). These matrices have to be symmetric, have to be the right size, and also have to satisfy the following conditions in order for the KF problem to have a solution:

\[Q_{o} \geq 0 \qquad\qquad R_{o}>0 \qquad\qquad M_{o}\geq 0.\]Just as with the LQR problem, this notation means is that $Q_{o}$ and $M_{o}$ are positive semidefinite and that $R_{o}$ is positive definite (see wikipedia).

By plugging in the expression for $n(t)$ that appears in the constraint, this optimal control problem can be rewritten as

\[\begin{aligned} \mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{x(t_{1}),d_{[t_{0},t_{1}]}} &\qquad (Cx(t_{0}) - y(t_{0}))^{T}M_{o}(Cx(t_{0}) - y(t_{0}))\\ &\qquad\qquad +\int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}} \left( (Cx(t) - y(t))^{T}Q_{o}(Cx(t) - y(t))+d(t)^{T}R_{o}d(t) \right) dt \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad \dot{x}(t) = Ax(t)+Bu(t)+d(t)\end{aligned}\]It is an optimal control problem, just like LQR—if you define

\[\begin{aligned} f(t,x,d) &= Ax+Bu(t)+d \\ g(t,x,d) &= (Cx-y(t))^{T}Q_{o}(Cx-y(t))+d^{T}R_{o}d(t) \\ h(t,x) &= (Cx-y(t))^{T}M_{o}(Cx-y(t))\end{aligned}\]then you see that this problem has the general form

\[\begin{aligned} \underset{x(t_1),d_{[t_0,t_1]}}{\text{minimize}} &\qquad h(t_0,x(t_{0}))+ \int_{t_{0}}^{t_{1}} g(t,x(t),d(t)) dt \\ \text{subject to} &\qquad \frac{dx(t)}{dt}=f(t,x(t),d(t)).\end{aligned}\]There are four differences between this form and the one we saw when solving the LQR problem:

-

The “input” in this problem is $u$, not $d$.

-

The “current time” is $t_{1}$ and not $t_{0}$.

-

The final state—i.e., the state at the current time—is not given. Indeed, the point here is to choose a final state $x(t_{1})$ that best explains $u(t)$ and $y(t)$.

-

The functions $f$, $g$, and $h$ vary with time (because they have parameters in them—$u(t)$ and $y(t)$—that are functions of time).

Because of these four differences, the HJB equation for a problem of this form is

\[0 = -\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{d} \left\{ -\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} f(t,x,d)+g(t,x,d) \right\}, \qquad v(t_{0},x) = h(t_{0}, x(t_{0})).\]Note the change in sign of both the first term outside the minimum and the first term inside the minimum—this is because we are effectively solving an optimal control problem in which time flows backward (from the current time $t_{1}$ to the initial time $t_{0}$, instead of from the current time $t_{0}$ to the final time $t_{1}$). It is possible to derive this form of the HJB equation in exactly the same way as it was done in the notes on LQR.

Solution to the problem

As usual, our first step is to find a function $v(t, x)$ that satisfies the HJB equation. Here is that equation, with the functions $f$, $g$, and $h$ filled in:

\[\begin{aligned} 0 &= -\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial t} + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{d} \biggl\{ -\frac{\partial v(t,x)}{\partial x} \left(Ax+Bu(t)+d\right) \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad +(Cx-y(t))^{T}Q_{o}(Cx-y(t))+d(t)^{T}R_{o}d(t) \biggr\} \\ v(t_{0},x) &= (Cx(t_{0})-y(t_{0}))^{T}M_{o}(Cx(t_{0})-y(t_{0})). \end{aligned}\]Expand the boundary condition:

\[\begin{aligned} v(t_{0},x) &= (Cx(t_{0})-y(t_{0}))^{T}M_{o}(Cx(t_{0})-y(t_{0})) \\ &= x(t_{0})^{T} C^{T}M_{o}C x(t_{0}) - 2 y(t_{0})^{T}M_{o}C^{T}x(t_{0}) + y(t_{0})^{T}M_{o}y(t_{0}) \end{aligned}\]This function has the form

\[v(t, x) = x^{T}P(t)x +2 o(t)^{T} x + w(t)\]for some symmetric matrix $P(t)$ and some other matrices $o(t)$ and $w(t)$ that satisfy the following boundary conditions:

\[P(t_{0}) = C^{T}M_{o}C \qquad o(t_{0}) = -CM_{o}y(t_{0}) \qquad w(t_{0}) = y(t_{0})^{T}M_{o}y(t_{0}).\]Let’s “guess” that this form of $v$ is the solution we are looking for, and see if it satisfies the HJB equation. Before proceeding, we need to compute the partial derivatives of $v$:

\[\frac{\partial v}{\partial t} = x^{T} \dot{P} x + 2 \dot{o}^{T} x + \dot{w} \qquad\qquad \frac{\partial v}{\partial x} = 2x^{T}P + 2o^{T}\]Here again—just as for LQR—we are applying matrix calculus. Plug these partial derivatives into HJB and we have

\[\begin{align*} 0 &= -\left(x^{T} \dot{P} x + 2 \dot{o}^{T} x + \dot{w}\right) + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{d} \biggl\{ -\left(2x^{T}P+ 2o^{T}\right) (Ax+Bu+d) \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad +(Cx-y)^{T}Q_{o}(Cx-y)+d^{T}R_{o}d \biggr\} \\ \tag{1} &= -\left(x^{T} \dot{P} x + 2 \dot{o}^{T} x + \dot{w}\right) + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{d} \biggl\{ d^{T}R_{o}d - 2(Px + o)^{T}d \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad -2 (x^{T} P+o^{T}) (Ax+Bu) \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad + (Cx-y)^{T}Q_{o}(Cx-y) \biggr\} \end{align*}\]To evaluate the minimum, we apply the first-derivative test (more matrix calculus!):

\[\begin{aligned} 0 &= \frac{\partial}{\partial d} \left( d^{T}R_{o}d - 2(Px + o)^{T}d -2 (x^{T} P+o^{T}) (Ax+Bu) + (Cx-y)^{T}Q_{o}(Cx-y) \right) \\ &= 2d^{T}R_{o}-2(Px+o)^{T}. \end{aligned}\]This equation is easily solved:

\[\begin{align*} \tag{2} d = R^{-1}(Px+o). \end{align*}\]Plugging this back into (1), we have

\[\begin{aligned} 0 &= -\left(x^{T} \dot{P} x + 2 \dot{o}^{T} x + \dot{w}\right) + \mathop{\mathrm{minimum}}_{d} \biggl\{ -\left(2x^{T}P+ 2o^{T}\right) (Ax+Bu+d) \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad +(Cx-y)^{T}Q_{o}(Cx-y)+d^{T}R_{o}d \biggr\} \\ &= -(x^{T} \dot{P} x + 2 \dot{o}^{T} x + \dot{w}) - (Px+o)^{T}R_{o}^{-1}(Px+o) \\ &\qquad\qquad -2 (x^{T} P+o^{T}) (Ax+Bu) + (Cx-y)^{T}Q_{o}(Cx-y) \\ &= x^{T}\left( -\dot{P} - PR_{o}^{-1}P -2PA + C^{T}Q_{o}C \right)x \\ &\qquad\qquad + 2x^{T} \left( -\dot{o} - PR_{o}^{-1}o - PBu -C^{T}Q_{o}y - A^{T}o \right) \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad +\left( -\dot{w} - o^{T}R_{o}^{-1}o -2o^{T}Bu + y^{T}Q_{o}y \right) \\ &= x^{T}\left( -\dot{P} - PR_{o}^{-1}P -PA - A^{T}P + C^{T}Q_{o}C \right)x \\ &\qquad\qquad + 2x^{T} \left( -\dot{o} - PR_{o}^{-1}o - PBu -C^{T}Q_{o}y - A^{T}o \right) \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad +\left( -\dot{w} - o^{T}R_{o}^{-1}o -2o^{T}Bu + y^{T}Q_{o}y \right) \end{aligned}\]where the last step is because

\[x^{T}(N+N^{T})x=2x^{T}Nx \text{ for any } N \text{ and } x.\]In order for this equation to be true for any $x$, it must be the case that

\[\begin{aligned} \dot{P} &= -PR_{o}^{-1}P-P A-A^{T}P +C^{T}Q_{o}C \\ \dot{o} &= - PR_{o}^{-1}o - PBu -C^{T}Q_{o}y - A^{T}o \\ \dot{w} &= - o^{T}R_{o}^{-1}o -2o^{T}Bu + y^{T}Q_{o}y. \end{aligned}\]In summary, we have found that

\[v(t, x) = x^{T}P(t)x +2 o(t)^{T} x + w(t)\]solves the HJB equation, where $P$, $o$, and $w$ are found by integrating the above ODEs forward in time, starting from

\[P(t_{0}) = C^{T}M_{o}C \qquad o(t_{0}) = -CM_{o}y(t_{0}) \qquad w(t_{0}) = y(t_{0})^{T}M_{o}y(t_{0}).\]The optimal choice of state estimate at time $t$ is the choice of $x$ that minimizes $v(t, x)$, that is, the solution to

\[\mathop{\mathrm{minimize}}_{x} \qquad x^{T}P(t)x +2 o(t)^{T} x + w(t).\]We can find the solution to this problem by application of the first derivative test, with some matrix calculus:

\[\begin{aligned} 0 &= \frac{\partial}{\partial x} \left( x^{T}Px +2 o^{T} x + w \right) \\ &= 2x^{T}P + 2o^{T}, \end{aligned}\]implying that

\[x = -P^{-1}o.\]Let’s call this solution $\widehat{x}$. Note that we can, equivalently, write

\[0 = P\widehat{x} + o.\]Suppose we take the time derivative of this expression, plugging in what we found earlier for $\dot{P}$ and $\dot{o},$ as well as plugging in yet another version of this same expression, $o = -P\widehat{x}$:

\[\begin{aligned} 0 &= \dot{P} \widehat{x} + P\dot{\widehat{x}} + \dot{o} \\ &= \left( -PR_{o}^{-1}P-P A-A^{T}P +C^{T}Q_{o}C \right)\widehat{x} + P\dot{\widehat{x}} - PR_{o}^{-1}o - PBu -C^{T}Q_{o}y - A^{T}o \\ &= -PR_{o}^{-1}P\widehat{x}-P A\widehat{x}-A^{T}P\widehat{x} +C^{T}Q_{o}C \widehat{x} + P\dot{\widehat{x}} + PR_{o}^{-1}P\widehat{x} - PBu -C^{T}Q_{o}y + A^{T}P\widehat{x} \\ &= P\dot{\widehat{x}} -PA\widehat{x}-PBu + C^{T}Q_{o}(C\widehat{x} - y) \\ &= P \left( \dot{\widehat{x}} - A\widehat{x} - Bu + P^{-1}C^{T}Q_{o}(C\widehat{x} - y) \right). \end{aligned}\]For this equation to hold for any $P$, we must have

\[\dot{\widehat{x}} = A\widehat{x} + Bu - P^{-1}C^{T}Q_{o}(C\widehat{x} - y).\]Behold! This is our expression for an optimal observer, if we define

\[L = P^{-1}C^{T}Q_{o}.\]Finally, suppose we take the limit as $t_{0}\rightarrow-\infty$, so assume an infinite horizon. It is a fact that $P$ tends to a steady-state value, and so $L$ does as well. When this happens, $\dot{P} = 0$, and so the steady-state value of $P$ is the solution to the algebraic equation

\[0 = -PR_{o}^{-1}P-P A-A^{T}P +C^{T}Q_{o}C.\]It is customary to write these last two equations in a slightly different way. In particular, suppose we pre- and post-multiply both sides of this last equation by $P^{-1}$, and define

\[P_{o} = P^{-1}\]Then, we have

\[L = P_{o}C^{T}Q_{o}\]and

\[0 = P_{o}C^{T}Q_{o}CP_{o}-AP_{o}-P_{o}A^{T} -R_{o}^{-1}.\]Summary

An optimal observer—a deterministic, infinite-horizon, continuous-time Kalman Filter—is given by

\[\dot{\widehat{x}} = A\widehat{x} + Bu - L(C\widehat{x} - y).\]where

\[L = P_{o}C^{T}Q_{o}\]and $P_{o}$ satisfies

\[0 = P_{o}C^{T}Q_{o}CP_{o}-AP_{o}-P_{o}A^{T} -R_{o}^{-1}.\]Comparison between LQR and KF (i.e., why you can use “LQR” in Python to compute an optimal observer)

An optimal controller is given by

\[u = -Kx\]where

\[\begin{align*} \tag{3} K = R_{c}^{-1}B^{T}P_{c} \end{align*}\]and $P_{c}$ satisfies

\[\begin{align*} \tag{4} 0 = P_{c}BR_{c}^{-1}B^{T}P_{c} - P_{c}A - A^{T}P_{c}-Q_{c}. \end{align*}\]An optimal observer is given by

\[\dot{\widehat{x}} = A\widehat{x} + Bu - L(C\widehat{x} - y).\]where

\[\tag{5} L = P_{o}C^{T}Q_{o}\]and $P_{o}$ satisfies

\[\tag{6} 0 = P_{o}C^{T}Q_{o}CP_{o}-AP_{o}-P_{o}A^{T} -R_{o}^{-1}.\]Take the transpose of (5) and—remembering that $P_{o}$ and $Q_{o}$ are symmetric—we get

\[\tag{7} L^{T} = Q_{o}CP_{o}.\]Take the transpose of (6) and—remembering that $R_{o}$ is also symmetric—we get

\[\tag{8} 0 = P_{o}C^{T}Q_{o}CP_{o}-P_{o}A^{T}-AP_{o} -R_{o}^{-1}.\]Compare (3) and (4) with (7) and (8). They are exactly the same if we make the following replacements:

-

replace $K$ with $L^{T}$

-

replace $A$ with $A^{T}$

-

replace $B$ with $C^{T}$

-

replace $Q_{c}$ with $R_{o}^{-1}$

-

replace $R_{c}$ with $Q_{o}^{-1}$

This is the reason why

L = lqr(A.T, C.T, linalg.inv(Ro), linalg.inv(Qo)).T

produces an optimal observer, just like

K = lqr(A, B, Qc, Rc)

produces an optimal controller. WWWWWOOOOOWWWWW!!!!!!!

Remember that:

import numpy as np

from scipy import linalg

def lqr(A,B,Q,R):

P=linalg.solve_continuous_are(A,B,Q,R)

K=linalg.inv(R) @ B.T @ P

return K